According to new research, fasting could help lower inflammation, a crucial factor in chronic diseases. Experts found that fasting boosts levels of arachidonic acid in the blood, which inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome, reducing inflammation. This insight sheds light on the anti-inflammatory effects of fasting and provides understanding of the advantages of calorie restriction in conditions such as obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and neurodegenerative disorders. The study also offers insights into how drugs like aspirin may function or their connection to diet, inflammation, and disease prevention.

Fasting increases arachidonic acid levels, which reduces NLRP3 inflammasome activity and inflammation. These findings may explain how fasting and calorie restriction can protect against chronic inflammation-related diseases. They also suggest a potential explanation for the anti-inflammatory effects of drugs like aspirin, which elevate arachidonic acid levels.

Scientists at the University of Cambridge have possibly discovered a new way that fasting helps reduce inflammation, which can be a harmful side effect of the body’s immune system and is linked to various chronic diseases. In a paper called “Arachidonic acid inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome is a mechanism to explain the anti-inflammatory effects of fasting,” published in Cell Reports, the team explains how fasting raises levels of a chemical in the blood known as arachidonic acid, which inhibits inflammation.

Fasting has been found to help decrease inflammation, but the underlying reasons were not clear. To address this, a team at the University of Cambridge and the National Institute for Health in the U.S. analyzed blood samples from 21 volunteers who ate a 500-kcal meal, fasted for 24 hours, and then had another 500-kcal meal.

When the researchers examined the effect of arachidonic acid on immune cells cultured in the lab, they discovered that it reduces the activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome. This was surprising, as previously arachidonic acid was thought to be associated with increased inflammation, not decreased levels.

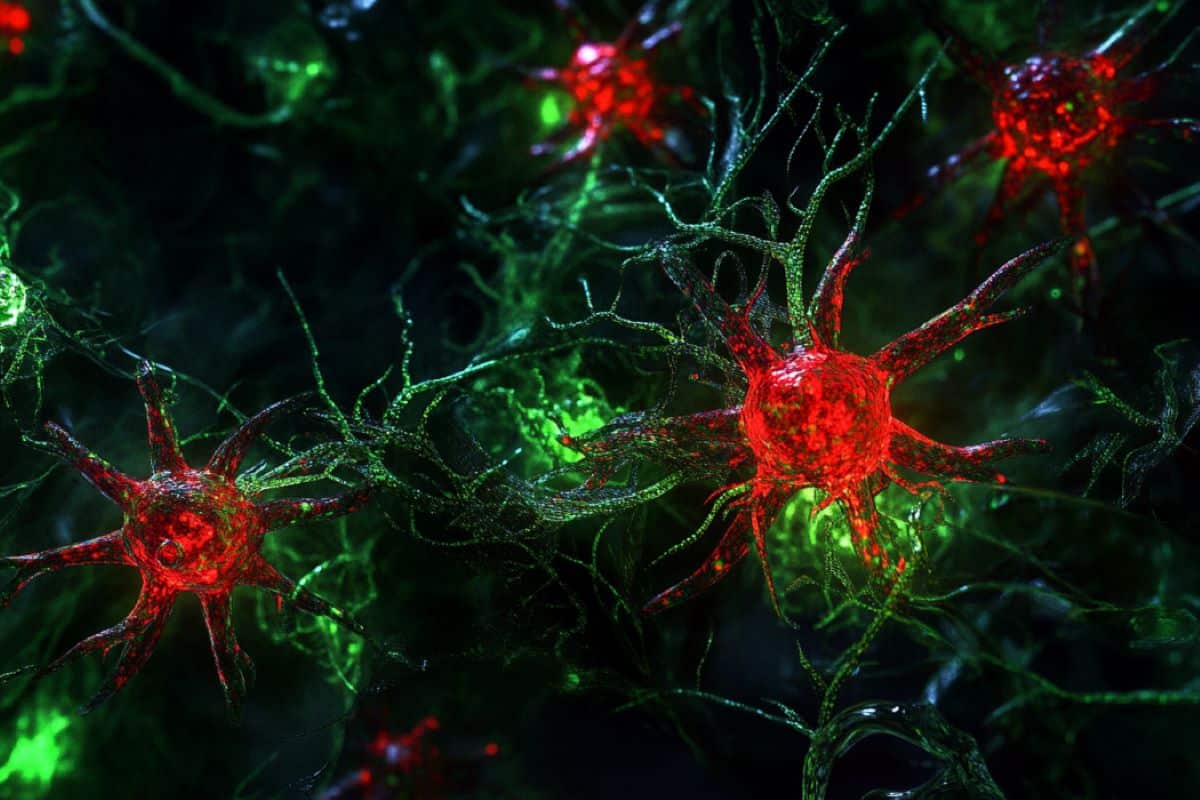

Professor Clare Bryant from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Medicine commented, “We’re very interested in trying to understand the causes of chronic inflammation in the context of many human diseases, and in particular the role of the inflammasome.” This inflammasome, known as the NLRP3 inflammasome, is particularly significant in diseases such as obesity, atherosclerosis, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s disease.

This study seeks to explain how changing our diet, particularly by fasting, protects us from inflammation, particularly the damaging form linked to many Western high-calorie diet-related diseases. While it’s too early to say whether fasting protects against diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, as the effects of arachidonic acid are short-lived, the work contributes to the growing scientific evidence highlighting the health benefits of calorie restriction.

Moreover, the research suggests a potential connection between a high-calorie diet and an increased risk of these diseases. Some patients with a high-fat diet have been found to have elevated levels of inflammasome activity. This research provides a potential explanation for how certain non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin work. Aspirin stops the rapid breakdown of arachidonic acid, leading to increased levels of arachidonic acid, which in turn reduces inflammasome activity and inflammation.

It is important to emphasize that aspirin should not be used to reduce the risk of long-term diseases without medical supervision, as it can have side effects such as stomach bleeds if taken over a long period.

About this diet and inflammation research news

Author: Clare Bryant

Source: University of Cambridge

Contact: Clare Bryant – University of Cambridge

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Arachidonic acid inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome is a mechanism to explain the anti-inflammatory effects of fasting” by Milton Pereira et al. Cell Reports

Fasting May Decrease Inflammation – Neuroscience News