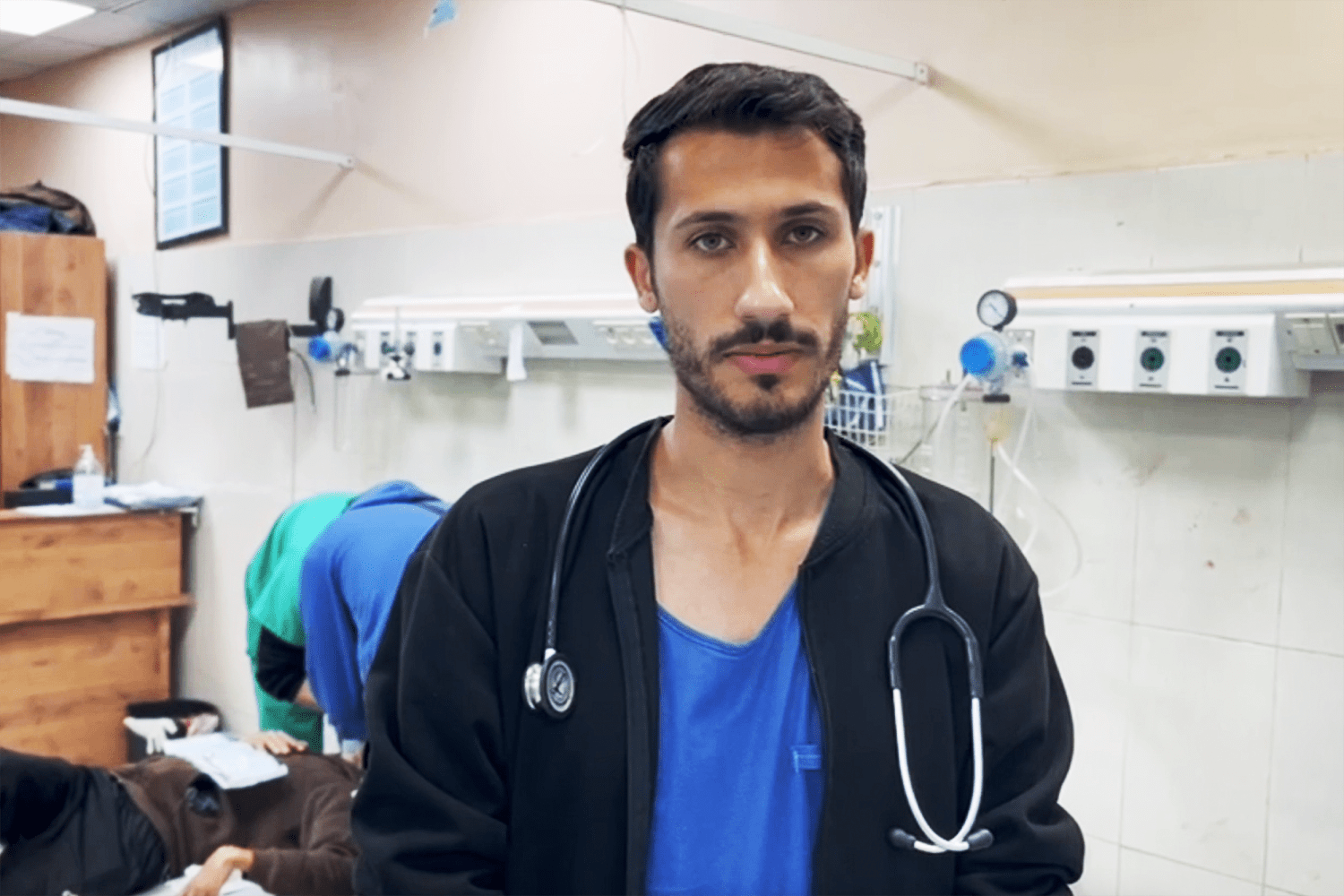

Dr. Muhammad Harara is one of only five doctors remaining in Nasser Hospital, the last major functioning medical facility in the Gaza Strip. The rest of his colleagues have either fled or been killed. Since the beginning of the war, an NBC News team has been following Harara and his fellow health workers on their hospital rounds, documenting how they deal with the seriously injured, the bloodied, and the terrified, all while being surrounded by Israeli soldiers and tanks.Harara, 27, with his sharp beard and lean features in rumpled blue scrubs, checks on patients lying on filthy, blood-stained floors who are increasingly being operated on with little or no anesthetic. Food and painkillers have run out. With the roads around Nasser Hospital a battlefield, thousands of people, including 850 patients, are trapped inside, according to the international charity Doctors Without Borders.Harara is a general practitioner who aspires to become a plastic surgeon. While consistently stoic and unexpressive on camera, he occasionally acknowledges that the death and destruction affect him.”We lost a lot of people today,” Harara said in the 16th week of the war, his emotionless words drained by weeks of violence. “I feel very, very sad for what happened today.”Israel has instructed residents in parts of Khan Younis, in southern Gaza, to evacuate the area after the military shifted its focus from the north to the south. Many people here have already been displaced at least once, having fled the north when Israel first launched its assault.The Israeli government and military claim they are targeting Hamas fighters in an effort to dismantle the militant group following its Oct. 7 attack, in which around 1,200 people were killed and another 240 abducted.More than 26,000 people across Gaza, the majority of whom are women and children, have been killed, according to local authorities, a figure supported by United States and United Nations officials. Follow live updatesIn Nasser Hospital, “death is everywhere,” Harara said on a recent day this month, when the Israel Defense Forces escalated its assault on Khan Younis.”The situation here is miserable and the smell of death is everywhere,” he told NBC News. “I feel like the Al-Shifa Hospital scenario is repeating itself,” Harara added, referring to the Gaza City hospital raided by Israeli troops in November, sparking international shock and alarm.Israel alleges that Hamas uses hospitals, including Al-Shifa, as bases for militants, a claim denied by Hamas and hospital staff. A U.S. intelligence assessment discovered that Al-Shifa was used to store some weaponry and house command infrastructure.Harara used to work at that hospital until he was forced to flee. His family is currently in Rafah, on Gaza’s border with Egypt, but he is unable to visit them “because of the siege,” he said.Harara says he cannot leave the hospital due to the encroaching war. Additionally, with patients still requiring treatment, he does not want to.NBC NewsThe corridors and rooms in Nasser Hospital are filled with people, some in worn clothes, others in hastily tied medical gowns. Many of the injured are agitated and wide-eyed; others stare blankly ahead. All await amid a cacophony of shouts and groans, interrupted by the rhythmic beep of hospital machines and the sounds of bombs and heavy gunfire nearby.On a recent day this month, Harara pushes a patient through the hospital, a gunshot victim he believes has internal bleeding in the chest cavity. A nurse calls for someone to bring blood; Harara requests a CT scan.”Today, like other days in this war, I spent all day in the emergency department,” Harara said. “A lot of injured came to the hospital. The situation was very, very bad.”Most of the cases he deals with involve amputations. But it’s not just the wounds from bombs and bullets.”We lack medical equipment and the simplest medication to deal with pain,” he said. “Many old diseases now appear recently in the hospital due to a lack of hygiene in the families who live in the hospital.”Providing insight into how rapidly the situation is deteriorating, cases of diarrhea among children in Gaza increased from 48,000 to 71,000 in just one week in December, Unicef, the U.N. children’s agency, said in a statement this month — equivalent to 3,200 new cases every day. The prewar average was 2,000 cases per week, according to Unicef.Its executive director, Catherine Russell, said that Gaza’s children were living through a “nightmare.”Harara arrived at Nasser after fleeing northern Gaza and his usual workplace, Al-Shifa Hospital, which has since been raided by Israeli troops.NBC NewsThe U.N. and humanitarian groups have condemned Israel’s campaign not only for the high civilian death toll, but for its destruction of hospitals, as well as other civilian sites such as schools, mosques, and bakeries. Israel blames Hamas, accusing it of hiding weapons and fighters at these locations and stating that, despite the risk of collateral damage, it has no choice but to target them.Harara witnesses the worst of this humanitarian crisis. But his hardship does not end when he leaves the hospital. His home in Khan Younis is now a flimsy plastic tarp near the hospital where he sleeps and eats with other men.After a day’s work, NBC News recently accompanied him as he walked near the hospital with a friend, chatting and checking the news on his phone. He bought some stale bread and a can of tuna from a young boy selling the tins from a makeshift stall and a broken plastic chair.He then paid coins to another street vendor pouring coffee into transparent plastic cups. Harara may have finished his shift but others had not; ambulances drove by while he bought his evening meal. Then Harara returned to his tarp to eat. His kitchen was a pop-up table, littered with debris and meager food supplies. The sun was setting, and this was his first meal since morning, a fast he broke by mixing the can of tuna and a lime, scooped up with a flatbread.He made tea on an electric stove powered by the nest of wires and multiple plugs dangling precariously in the corner, fueled by the limited electricity supply available to Gazans.”I come to the tent to eat something after a hard day at the hospital,” he said with considerable impassiveness on a day in which he claims to have seen nine patients die. “I haven’t eaten anything since the start of the day. Now I am very hungry.”Alexander Smith is a senior reporter for NBC News Digital based in London.

Inside Gaza’s Nasser Hospital, surrounded by Israeli forces