## Jerome Powell: Full 2024 60 Minutes interview transcript

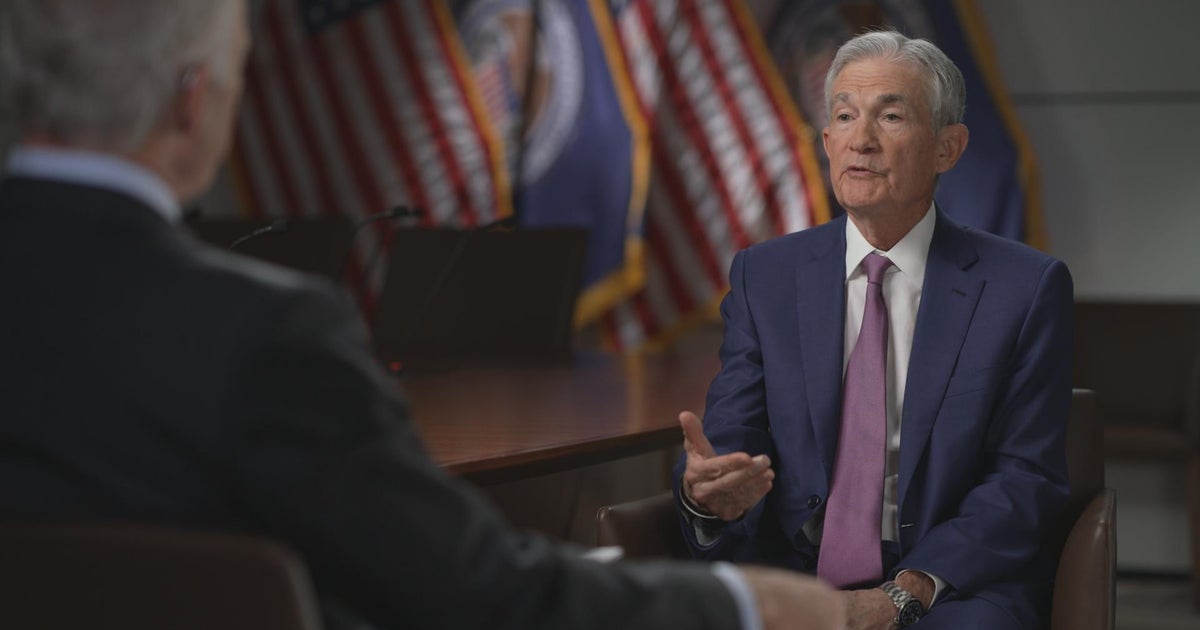

Editor’s Note: On Feb. 1, 2024, 60 Minutes correspondent Scott Pelley interviewed Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell in the Board Room at the Federal Reserve headquarters in Washington, D.C. Below is the transcript of that interview.

SCOTT PELLEY, CBS NEWS/60 MINUTES: I’ll start with this. Is inflation dead?

FEDERAL RESERVE CHAIR JEROME POWELL: I wouldn’t go quite so far as that. What I can say is that inflation has come down really over the past year, and fairly sharply over the past six months. We’re making good progress. The job is not done and we’re very much committed to making sure that we fully restore price stability for the benefit of the public.

PELLEY: But inflation has been falling steadily for 11 months.

POWELL: Right.

PELLEY: You’ve avoided a recession. Why not cut the rates now?

POWELL: Well, we have a strong economy. Growth is going on at a solid pace. The labor market is strong: 3.7% unemployment. And inflation is coming down. With the economy strong like that, we feel like we can approach the question of when to begin to reduce interest rates carefully.

PELLEY: What is it you’re looking at?

POWELL: Basically, we want to see more good data. It’s not that the data aren’t good enough. It’s that there’s really six months of data. We just want to see more good data along those lines. It doesn’t need to be better than what we’ve seen, or even as good. It just needs to be good. And so, we do expect to see that. And that’s why almost every single person on the, on the Federal Open Market Committee believes that it will be appropriate for us to reduce interest rates this year.

PELLEY: When?

POWELL: Well, that will depend on the data. You know, the best we can do is to weigh the risk of moving too soon against the risk of moving too late and make that judgment in real time. So that time is coming, I would say, based on what we expect. The kinds of things that would make us want to move sooner would be if we saw weakness in the labor market or if we saw inflation really persuasively coming down. The kind of things that would make us want to move later would be if inflation were to be more persistent, for example.

PELLEY: What’s the danger of moving too soon?

POWELL: Danger of moving too soon is that the job’s not quite done, and that the really good readings we’ve had for the last six months somehow turn out not to be a true indicator of where inflation’s heading. We don’t think that’s the case. But the prudent thing to do is to, is to just give it some time and see that the data continue to confirm that inflation is moving down to 2% in a sustainable way.

PELLEY: Moving too soon would set off inflation again.

POWELL: You could. Or you could just halt the progress. I think more likely if you move too soon, you’d see inflation settling out somewhere well above our 2% target. So, we think we can be careful in approaching this decision just because of the strength that we’re seeing in the economy.

PELLEY: And what is the danger of moving too late?

POWELL: If you move too late, then policy would be too tight. And that could easily weigh on economic activity and on the labor market.

PELLEY: Making a recession.

POWELL: Right. And we have to, we have to balance those two risks. There is no, you know, easy, simple, obvious path. We have to balance the risk of moving too soon, which, as you mentioned, or too late. And there are different risks. We think the economy’s in a good place. We think inflation is coming down. We just want to gain a little more confidence that it’s coming down in a sustainable way toward our 2% goal.

PELLEY: You disappointed a lot of people on Wednesday.

POWELL: We’re very focused on our jobs, you know? We’re focused on the real economy and doing the right thing for the economy and for the American people over the medium and long term. And I can’t overstate how important it is to restore price stability, by which I mean inflation is low and predictable and people don’t have to think about it in their daily lives. In their daily economic lives, inflation is just not something that you talk about. That’s where we were for 20 years. We want to get back to that, and I think we are on a path to that. We just want to kind of make sure of it.

PELLEY: Why is your target rate 2%?

POWELL: So over, really over the course of the last few decades, central banks around the world have adopted – advanced economy central banks have adopted a 2% target. Why isn’t it zero, I guess, is the question. And the reason is 2% is if interest rates always include an estimate of future inflation. If that estimate is 2%, that means you’ll have 2% more that you can cut in interest rates. The central bank will have more ammunition, more power to fight a downturn if rates are a little bit higher. In any case, that’s become the global norm. And it’s a pretty stable equilibrium and it seems to serve the public well.

PELLEY: Are you committed to getting all the way to 2.0 before you cut the rates?

POWELL: No, no. That’s not what we say at all, no. We’re committed to returning inflation to 2% over time. I’ve said that we wouldn’t wait to get to 2% to cut rates. In fact, you know, we’re actively considering now going forward cutting rates, and on a 12-month basis inflation, you know, is not at 2%. It’s between 2-3%. But it’s moving down in a way that, that it gives us some comfort.

PELLEY: So what is your best forecast for inflation right now?

POWELL: I think the base case, the main expectation I would have, is that inflation will continue to move down in the first six months of this year, we expect. So, we look at inflation over a 12-month basis. That’s our target. And the first five months of last year were fairly high readings. Those are going to fall out of the 12-month window and be replaced by lower readings. So, I do expect that you will see the 12-month inflation readings coming down over the course of this year. We’ve seen inflation pressures subsiding really for a couple of reasons. One is the reversal, the unwinding of these unusual pandemic-related distortions to both, to both supply and demand. And the other is our tightening of policy, which was absolutely essential in getting — it’s a part of the story for why inflation’s coming down. Not the whole story, by far.

PELLEY: Inflation is one thing. Prices are another. And I wonder if there’s any reason to believe that people will see the prices of things decline?

POWELL: So, the prices of some things will decline. Others will go up. But we don’t expect to see a decline in the overall price level. That doesn’t tend to happen in economies, except in very negative circumstances. What you will see, though, is inflation coming down. People are experiencing high prices. If you think about the basic necessities, things like, you know, bread and milk and eggs and meats of various kinds, if you look back, prices are substantially higher than they were before the pandemic. And so, we think that’s a big reason why people are, have been relatively dissatisfied with what is otherwise a pretty good economy.

PELLEY: But those prices will not soften short of something like a recession?

POWELL: Some of them will. In particular, things that are affected by commodity prices, like, for example, gasoline prices have come way down. Some food prices that incorporate the price of commodities, grains and things like that, those can come down. But the overall price level doesn’t come down. It will fluctuate. And some goods will, goods and services will go up, others will go down. But overall, in aggregate, the price level doesn’t tend to go down except in fairly extreme circumstances.

PELLEY: Many in the financial industry expect you to lower rates sitting around this table in your [next] meeting in March.

POWELL: So we’re very focused on doing the right thing for the economy in the medium and the longer term. Of course we pay attention to markets and we understand what’s going on in financial markets around the world, really. It’s part of our job.

PELLEY: The next meeting around this table that will decide the direction of interest rates is in this coming March. Knowing what you know now, is a rate cut more likely or less likely at that time?

POWELL: So, the broader situation is that the economy is strong, the labor market is strong, and inflation is coming down. And my colleagues and I are trying to pick the right point at which to begin to dial back our restrictive policy stance. That time is coming. We’ve said that we want to be more confident that inflation is moving down to 2%. And I would say, and I did say yesterday, that I think it’s not likely that this committee will reach that level of confidence in time for the March meeting, which is in seven weeks. So, I would say that’s not the most likely or base case. However, all but a couple of our participants do believe it will be appropriate for us to begin to dial back the restrictive stance by cutting rates this year. And so, it is certainly the base case that, that we will do that. We’re just trying to pick the right time, given the overall context.

PELLEY: This past December in your quarterly report, the Fed predicted rate cuts this year down to about 4.6%. Still likely?

POWELL: Those forecasts were made in December. And those are individual forecasts made by participants. It’s not a committee plan. We don’t update those at every meeting. We’ll update them at the March meeting. I will say, though, nothing has happened in the meantime that would lead me to think that people would dramatically change their forecasts. So something around a 4.6% interest rate is likely?

POWELL: I would say it this way. It’s really going to depend on the data. The data will drive these decisions. And we can’t do any better than to look at the data and ask ourselves, “How is this affecting the outlook and the balance of risks?” That’s what we’ll be doing. So, what we actually do will depend on how the economy evolves.

PELLEY: How would you characterize the consensus around this table for rate cuts? Is everyone onboard? Most people?

POWELL: Almost all. Almost all of the 19 participants who sit around this table believe that it will be appropriate in their most likely case for us to cut the federal funds rate this year. So, the consensus, though, the thing that really comes out in people’s thinking as we discuss this around the table, is that what we actually do is really going to depend on the evolution of the economy. So, if the economy were to weaken, then we could reduce rates earlier and perhaps faster. If the economy were to prove — if inflation were to prove more persistent, that could call for us to reduce rates later and perhaps slower. So, it really is going to be dependent on the incoming data as that affects the outlook.

PELLEY: Your decisions inevitably are going to have a bearing on this year’s election. And I wonder, to what degree does politics determine your timing?

POWELL: We do not consider politics in our decisions. We never do. And we never will. And I think the record — fortunately, the historical record really backs that up. People have gone back and looked. This is my fourth presidential election in the Fed, and it just doesn’t come into our thinking, and I’ll tell you why. Two reasons. One, we are a non-political organization that serves all Americans. It would be wrong for us to start taking politics into account. Secondly, though, it’s not easy to get the economics of this right in the first place. These are complicated, you know, risk-balancing decisions. If we tried to incorporate a whole ‘nother set of factors in politics into those decisions, it could only lead to worse economic outcomes. So, we simply don’t do that, and we’re not going to do it. We haven’t done it in the past, and we’re not going to do it now.

PELLEY: There are people watching this interview who are skeptical about that.

POWELL: You know, I would just say this. Integrity is priceless. And at the end, that’s all you have. And we in, we plan on keeping ours.

PELLEY: As you look toward adjusting rates, what are the specific factors in the economy that are going to guide that decision?

POWELL: So, we look at the totality of economic activity, in particular I’ll point to two things. One just is the progress of inflation, what’s happening with inflation. What’s the story behind the numbers that we’re seeing? Are we see[ing] continuing progress down to 2%? Does it give us more confidence that we’re on a sustainable path to 2%? That’s a critical thing. The second thing is, you know, we are dual-mandate central bank. We have a maximum employment mandate which is equal to our price stability mandate. So, we’ll be looking at lots of labor market data to reach a judgment about the ongoing strength of the labor market. So right now, what we’re seeing in the labor market is a very strong labor market. But it’s one that’s been coming back into better balance. If you go back a couple of years ago, there was an extreme labor shortage, and the labor market was overheating. And businesses couldn’t find workers. We lost several million people who were not in the labor force after the pandemic. We’re in a much better place now. The people have come back into the labor force. There are more workers. And the labor market is well along the road of getting back to a better balance. And we’ll be watching those things.

PELLEY: You said that you were watching the story behind the numbers. What do you mean by that?

POWELL: So, sometimes things happen which tell you a lot about the real direction of things. And sometimes they seem idiosyncratic or transitory. And which means that they will go away quickly without any action on our part. So, we have to judge that. Looking at any set of economic data, you’ve got to ask yourself, “OK, how much — what’s this telling me about the future?” What is the past. That’s the rearview mirror. What we’re always trying to ascertain is what’s going to happen going forward. And that’s not easy. But you’ve got to distinguish between [those] that will have persistent effects and those that won’t. So, the story does matter. For example, with inflation, we break it down into goods inflation, housing services inflation, and non-housing services inflation. Behind each of those three buckets, there’s a lot going on. And they, together — we don’t care what the allocation is, but together they’ve got to put together a story that says that inflation is coming back down to 2%. And by the way, we think it is. We think we’re making this progress. It’s just we want more confidence in that. We think we best serve the public by having a little more confidence before we make this important step.

PELLEY: I’m curious. Do you, Mr. Chairman, have a favorite metric that you look at to keep your finger on the pulse of the economy?

POWELL: A single metric? I might be able to limit myself to 20 metrics. I could not identify a single one. I would say, you know, with the labor market there’s so much. The labor market is the place where we have lots and lots of data, and better-quality data than a lot of places. And so all of us follow many things. Inflation we tend to target. Headline inflation, which is total inflation including, you know, energy and food prices, that’s our target. But we look at core inflation, which excludes energy and food prices because that tends to be a better indication of where things are going.

PELLEY: Why did inflation surge in 2021?

POWELL: You know, it’s a complicated story as usual with economics. So, there were a number of factors. And I would say one big factor was just the effects of the pandemic. We did see inflation break out all over the world. And really, it was this unique event in modern history where the economy shut down briefly and then reopened. And there were big effects in many countries, including in the United States, on the number of workers that were available. But when the economy reopened, there was a lot of pent-up demand. In addition, the things people spent money on, they couldn’t spend money during the pandemic on in-person services. So, no restaurants and things like that. So, they bought a lot, a lot of goods. So that was, all of those things were big. I think also, you know, there’s certainly a role for fiscal policy, which supported people. Those are all for monetary policy, which supported the economy. There are many, many things. And I would say the same thing on the other side. Now that inflation’s coming down, that too, is a story where there are many factors at work in having inflation come down.

PELLEY: There was a stupendous amount of government spending. To support the economy.

POWELL: Well, there was. You know, we had a situation where the CARES Act was passed unanimously by the House and Senate. I wonder if, when the last time that happened or the next time will be. Extraordinarily unusual. And it was because the pandemic really was so unique and the range of possible outcomes was broad, and not in a good way. We didn’t know how quickly there would be vaccines, for example. It could’ve been years. We didn’t know how lethal the pandemic would be. So, people were very concerned about the economy. Congress really stepped up, and we really stepped up, and you know, inflation came in March of 2021. And so that, that’s really what happened. But it was a lot of different factors, some of which are just attributable to the shutting and reopening of the economy.

PELLEY: Was the Fed too slow to recognize inflation in 2021?

POWELL: So in hindsight, it would’ve been better to have tightened policy earlier. I’m happy to say that. Really, it was this. We saw what we thought was that this inflation, which seemed to be mostly limited to the goods sector and to the supply chain story. We thought that the economy was so dynamic that it would fix itself fairly quickly. And we thought that inflation