Back in 1993, I started as a Nightly News intern at 30 Rockefeller Center with the aspiration of becoming a network correspondent, traveling the world, and making a positive impact by highlighting the needs of others. This has been my dream job, and it would take something significant to make me change directions: if it’s best for my family, best for my health, or if it gives me the opportunity to make a larger-scale impact. Today, these three things are aligning. My health is good. My cancer is in remission, but as a breast cancer survivor, the fear of a recurrence always lingers. This fear is why meeting Dr. Nora Disis last fall filled me with hope. Disis is a researcher at UW Medicine’s Cancer Vaccine Institute and is among a small group of doctors making strides in the field of breast cancer vaccines. “Can you imagine a world where no one would die of breast cancer because of a vaccine?” Disis asked me. This question did not come as a surprise to me — and it’s not a far-fetched idea.

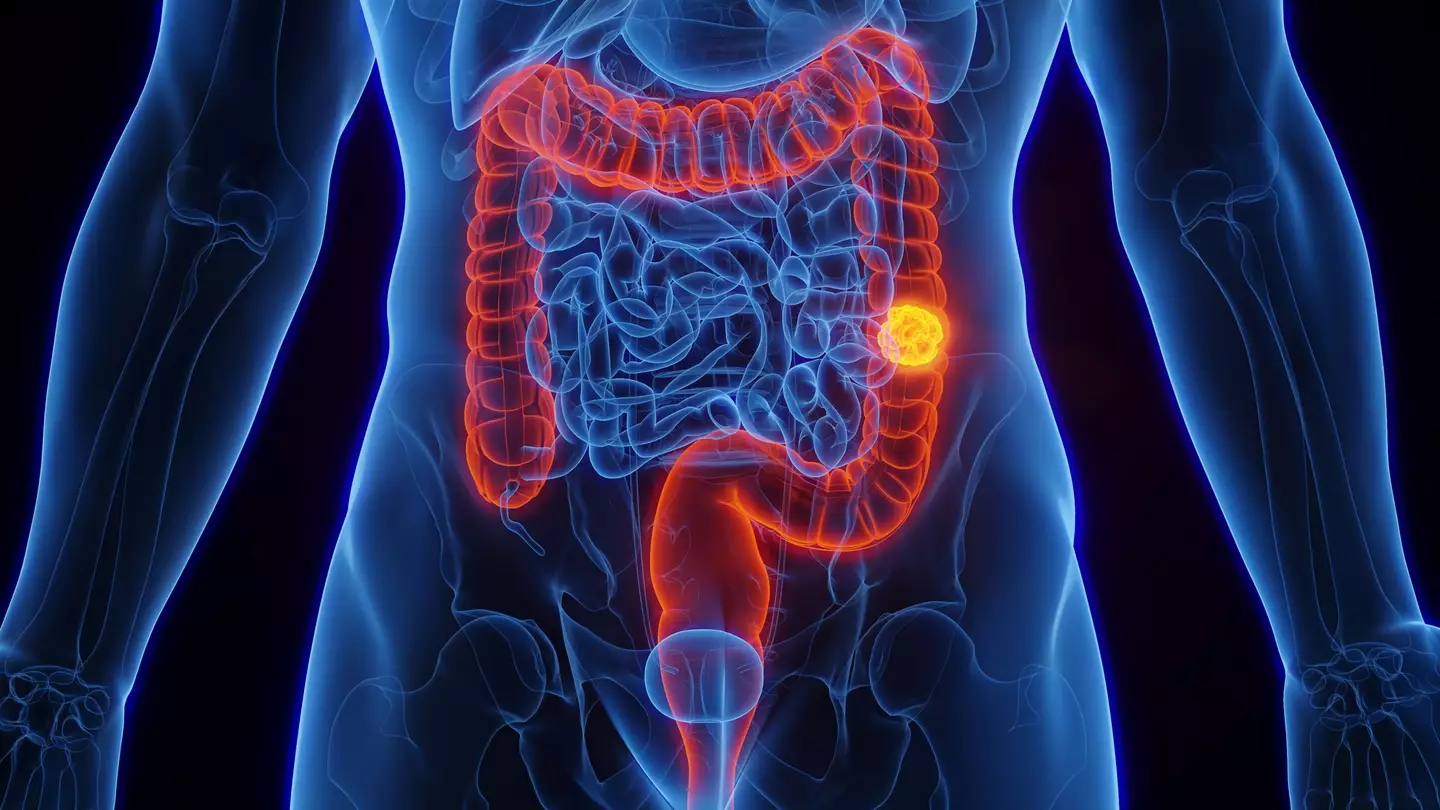

I’ve spent the last four months investigating and connecting with top cancer researchers and oncologists across the country. In 2013, Disis and her team made headlines with a promising trial involving 66 women with advanced-stage HER2-positive breast cancer. The trial was not aimed at evaluating whether the vaccine could slow or prevent the progression of breast cancer, but the researchers observed that many of the participants lived longer than expected. Normally, about half of people with this type of cancer at these stages would be expected to die within five years of the treatment. Among those who received the optimal vaccine dose, 80% were still alive at the 10-year mark.

This month, I went to Seattle to visit the Cancer Vaccine Institute’s lab, meet Disis, and talk to one of the trial participants, Brigette Hempstead. In 2013, Hempstead’s breast cancer had spread to her lungs and liver, and her oncologist had given her a year to live. Instead of accepting her fate, she joined the vaccine trial. Now, Hempstead reports having periods with no signs of the disease, and when her scans reveal cancer, “they’re going away. They’re disappearing,” she says. Hempstead explains, “the way that this vaccine works is…if the cancer comes up, then (the vaccine) shows up and really tries to help fight it.”

According to Disis, understanding how to elicit that immune response and which parts of breast cancer can be targeted to eliminate tumors are reasons she believes we are on the verge of developing vaccines to eradicate breast cancer. Disis and her team are currently working on STEMVAC, a vaccine candidate designed to target cancer stem cells that are not reached by chemotherapy or radiation. The vaccine is already in phase 2 trials.

The Cancer Vaccine Institute is not the only institution conducting this groundbreaking work. The Cleveland Clinic and Anixa Biosciences recently shared encouraging data from a phase 1 trial of a vaccine for aggressive triple-negative breast cancer, which is known as a difficult cancer to treat. The majority of patients developed the intended T-cell responses with no negative side effects. Jenni Davis was the first person in the world to receive Cleveland Clinic’s vaccine. As a nurse, she was well aware of the grim reality of a triple-negative diagnosis. “I wanted to see my kids grow into adults and… get married and have kids, and I was just, I was very scared and worried that … those things weren’t going to happen for me,” she recently told me. She was elated to qualify for Cleveland Clinic’s vaccine trial in 2019. She received the doses and reports that her only side effects were lumps at the injection site. Doctors confirm that she had a positive immune response. She echoes what Brigette Hempstead and the doctors also told me. “The vaccine has taught my body to identify those cells and destroy them before they can become a tumor,” Davis says.

While there is scientific evidence, there is also an indescribable emotional impact for Davis. “It’s given me hope for myself and my family,” she says, adding that “the bigger picture is what this could mean for breast cancer…it could change everything.”

This sentiment was previously out of reach, but Disis says that’s what they are now striving for — to have vaccines for all breast cancer patients and those at high risk. “What we really need is to be able to evaluate these vaccines in a very uniform manner with a lot of eyes looking at the data coming out of these trials,” Disis explains. “We are all working in our individual silos… but if we collaborated, we could get this done in five to ten years instead of 30.” Dr. Tom Budd, a physician at the Cleveland Clinic, shares the same optimism. “I am definitely encouraged, there are immune responses being produced,” he says, but he also cautions that “to really demonstrate this in a highly reproducible way, we need large studies. And that’s why we need collaboration so we can do the big studies that will prove what works.”

This reasoning resonated with me, prompting my wholehearted commitment when another breast cancer survivor I interviewed in 2022 approached me with an idea to do just that. Michele Young, an Ohio lawyer and stage 4 breast cancer survivor, was once advised to go home and start checking off items from her bucket list. Today, she is in complete remission and is dedicated to ensuring that all individuals have access to effective and timely screenings for breast cancer. She played a pivotal role in Ohio passing legislation guaranteeing additional screening for dense breasts and ensuring coverage by insurance. Now, she is focusing on vaccines, and together, we established a nonprofit called the Pink Eraser Project. This initiative aims to bring together the leading minds in the nation to expedite the development of breast cancer vaccines.

Kristen Dahlgren: My Decision to Leave NBC and Launch a Nonprofit for Making Breast Cancer Vaccines a Reality