Since humans first started using fire, they’ve been curious about why insects are so attracted to light. With the use of electricity, this mystery has become even more important as artificial lights disrupt insect behavior worldwide. Scientists have now discovered why insects are drawn to the flame. Credit: Sam FabianScientists have found that insects tend to keep their backs to light sources at night, indicating that artificial lights disrupt their natural navigation. This discovery challenges long-held beliefs and emphasizes the impact of artificial lighting on insect behavior and conservation.In the Costa Rican cloud forest at night, a team of international scientists observed insects congregating around a light source. Moths with eye-like spots on their wings, shiny armored beetles, flies, and even a praying mantis joined in the mesmerizing dance around the light bulb. This phenomenon, while not new to the researchers, was now being studied with cutting-edge technology and high-speed cameras capable of capturing the fast, erratic movements of hundreds of insects.

Since humans first started using fire, they’ve been curious about why insects are so attracted to light. With the use of electricity, this mystery has become even more important as artificial lights disrupt insect behavior worldwide. Scientists have now discovered why insects are drawn to the flame. Credit: Sam FabianScientists have found that insects tend to keep their backs to light sources at night, indicating that artificial lights disrupt their natural navigation. This discovery challenges long-held beliefs and emphasizes the impact of artificial lighting on insect behavior and conservation.In the Costa Rican cloud forest at night, a team of international scientists observed insects congregating around a light source. Moths with eye-like spots on their wings, shiny armored beetles, flies, and even a praying mantis joined in the mesmerizing dance around the light bulb. This phenomenon, while not new to the researchers, was now being studied with cutting-edge technology and high-speed cameras capable of capturing the fast, erratic movements of hundreds of insects. The research project began in Lin’s lab, where Fabian works and has a motion capture arena, equivalent to those used in movies, but on an insect scale. Credit: Sam FabianThe team made a surprising observation: while in flight, the insects consistently turned their backs to the artificial light source.”When you watch the videos in slow motion, you can see it happening repeatedly,” said Yash Sondhi, a recent FIU biological sciences Ph.D. graduate and current postdoctoral researcher at the Florida Museum of Natural History. “Even though it may appear to people that they are flying directly at the light around their porch or a streetlamp, that’s not the case.”This previously undocumented behavior, which has been published in the journal Nature Communications, offers a new explanation for the disruptive effect of light on insects and provides new insight into conservation concerns. Little markers in the shape of an L were attached to the backs of several moths and dragonflies, allowing the researchers to collect data on how these insects rolled, rotated, and moved through three-dimensional space when flying around light. Credit: Sam FabianInsects have evolved over millions of years to become skilled fliers by relying on the brightest object they see, which is typically the sky. However, the artificial lights of the modern world confuse their instincts. Insects mistake the artificial “sky” for the real one and become trapped in a futile effort to maintain their orientation, resulting in clumsy maneuvers and occasional crashes into the light source.Gravity is crucial for all animals, especially flying insects, who experience rapid acceleration during flight, making their gravity sensing unreliable. They rely on the sky, even at night, to determine their orientation and maintain control in the air. Artificial light disrupts this system.Sondhi began to see the connection between insect vision, light, and flight when he joined FIU associate professor of biology Jamie Theobald’s lab in 2017. The research gained momentum when he found a group of specialists in the fields of insect flight and sensory systems who were eager to analyze a vast amount of 3D flight data in search of revelations.

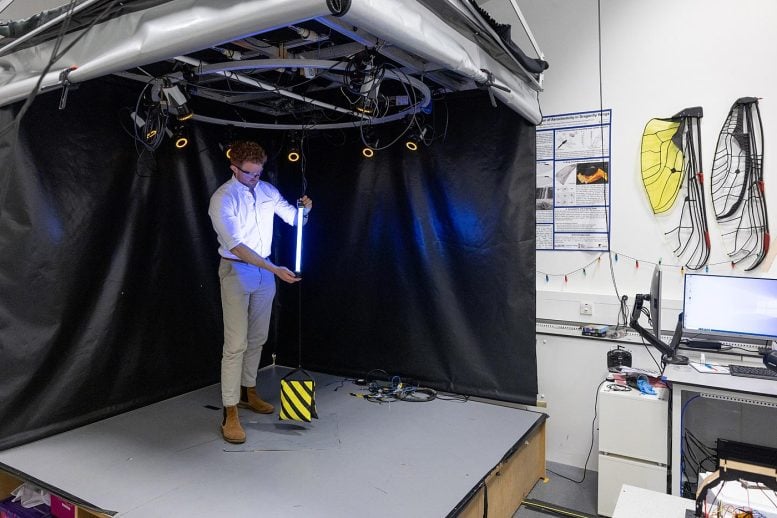

The research project began in Lin’s lab, where Fabian works and has a motion capture arena, equivalent to those used in movies, but on an insect scale. Credit: Sam FabianThe team made a surprising observation: while in flight, the insects consistently turned their backs to the artificial light source.”When you watch the videos in slow motion, you can see it happening repeatedly,” said Yash Sondhi, a recent FIU biological sciences Ph.D. graduate and current postdoctoral researcher at the Florida Museum of Natural History. “Even though it may appear to people that they are flying directly at the light around their porch or a streetlamp, that’s not the case.”This previously undocumented behavior, which has been published in the journal Nature Communications, offers a new explanation for the disruptive effect of light on insects and provides new insight into conservation concerns. Little markers in the shape of an L were attached to the backs of several moths and dragonflies, allowing the researchers to collect data on how these insects rolled, rotated, and moved through three-dimensional space when flying around light. Credit: Sam FabianInsects have evolved over millions of years to become skilled fliers by relying on the brightest object they see, which is typically the sky. However, the artificial lights of the modern world confuse their instincts. Insects mistake the artificial “sky” for the real one and become trapped in a futile effort to maintain their orientation, resulting in clumsy maneuvers and occasional crashes into the light source.Gravity is crucial for all animals, especially flying insects, who experience rapid acceleration during flight, making their gravity sensing unreliable. They rely on the sky, even at night, to determine their orientation and maintain control in the air. Artificial light disrupts this system.Sondhi began to see the connection between insect vision, light, and flight when he joined FIU associate professor of biology Jamie Theobald’s lab in 2017. The research gained momentum when he found a group of specialists in the fields of insect flight and sensory systems who were eager to analyze a vast amount of 3D flight data in search of revelations. Insects flew in complex revolutions around an artificial light source, keeping their backs to the bulb, which they seem incapable of distinguishing from the night sky. Credit: Sam FabianThe research team, comprised of Sondhi, Theobald, Fabian, Lin, and Allen, set up lights beneath the canopy of a tropical rainforest in Costa Rica to study the flight behaviors of insects. They collected over 477 videos capturing the flight paths of more than 11 insect orders and used computer tools to reconstruct these paths in three dimensions. Analysis of this data confirmed that all species of insects observed flipped upside down when exposed to light, similar to the large yellow underwing moth in the lab.

Insects flew in complex revolutions around an artificial light source, keeping their backs to the bulb, which they seem incapable of distinguishing from the night sky. Credit: Sam FabianThe research team, comprised of Sondhi, Theobald, Fabian, Lin, and Allen, set up lights beneath the canopy of a tropical rainforest in Costa Rica to study the flight behaviors of insects. They collected over 477 videos capturing the flight paths of more than 11 insect orders and used computer tools to reconstruct these paths in three dimensions. Analysis of this data confirmed that all species of insects observed flipped upside down when exposed to light, similar to the large yellow underwing moth in the lab. To test their theory in the wild, the team traveled to the Estación Biológica Monteverde in Costa Rica, where they set up lights beneath the canopy of a tropical rainforest. Credit: Yash Sondhi”This has been a prehistorical question. In the earliest writings, people were noticing this around fire,” Theobald remarked. “It turns out all our speculations about why it happens have been wrong, so this is definitely the coolest project I’ve been part of.”While the study confirms that light disrupts insects, it also suggests that the direction and type of light matter. Lights facing upwards or uncovered are found to have the most negative impact. Therefore, shrouding or shielding the light may be crucial in mitigating the effects on insects. The team is also considering the impact of light color and the mystery behind insects’ attraction to light over long distances.”I’d been told before you can’t ask why questions like this one, that there was no point,” Sondhi said. “But in being persistent and finding the right people, we came up with an answer none of us really thought of, but that’s so important to increasing awareness about how light impacts insect populations and informing changes that can help them out.”Reference: “Why flying insects gather at artificial light” by Samuel T. Fabian, Yash Sondhi, Pablo E. Allen, Jamie C. Theobald and Huai-Ti Lin, 30 January 2024, Nature Communications.

To test their theory in the wild, the team traveled to the Estación Biológica Monteverde in Costa Rica, where they set up lights beneath the canopy of a tropical rainforest. Credit: Yash Sondhi”This has been a prehistorical question. In the earliest writings, people were noticing this around fire,” Theobald remarked. “It turns out all our speculations about why it happens have been wrong, so this is definitely the coolest project I’ve been part of.”While the study confirms that light disrupts insects, it also suggests that the direction and type of light matter. Lights facing upwards or uncovered are found to have the most negative impact. Therefore, shrouding or shielding the light may be crucial in mitigating the effects on insects. The team is also considering the impact of light color and the mystery behind insects’ attraction to light over long distances.”I’d been told before you can’t ask why questions like this one, that there was no point,” Sondhi said. “But in being persistent and finding the right people, we came up with an answer none of us really thought of, but that’s so important to increasing awareness about how light impacts insect populations and informing changes that can help them out.”Reference: “Why flying insects gather at artificial light” by Samuel T. Fabian, Yash Sondhi, Pablo E. Allen, Jamie C. Theobald and Huai-Ti Lin, 30 January 2024, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-44785-3

Moths to a Flame: Millennia-Old Mystery About Insects and Light at Night Solved at Last