New research indicates that modern humans migrated over the Alps and into the frigid Northern Europe around 45,000 years ago, coexisting with Neanderthals for an extended period. The findings document the oldest known Homo sapiens remains in Central and Northwest Europe, with 13 bone fragments unearthed from a cave in Germany, dating back approximately 44,000 to 47,500 years. The discovery is surprising considering the harsh climatic conditions in the region at the time. Archaeologist Sarah Pederzani, who led the paleoclimate study of the site, commented that early Homo sapiens dispersing across Eurasia showed capacity to adapt to extreme climatic conditions.Related: Modern humans migrated into Europe in 3 waves, ‘ambitious and provocative’ new study suggests The arrival of H. sapiens in Europe occurred after Neanderthals, who occupied the continent from around 200,000 years ago until their extinction roughly 40,000 years ago. Previous research indicated the presence of H. sapiens in Southwest Europe by 46,000 years ago. Much debate surrounds the interactions between H. sapiens and Neanderthals during the Middle-to-Upper Paleolithic transition period (47,000 to 42,000 years ago), and the potential role of H. sapiens in the decline of Neanderthals.The investigations of three new studies focused on artifacts and the climate from that transitional period. Archaeologists have previously identified various stone tool manufacturing styles from this time, such as the Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician (LRJ) industry, and questioned whether they were crafted by H. sapiens or Neanderthals.”The Middle Paleolithic in Europe [about 300,000 to 35,000 years ago] is linked with Neanderthals, while the Upper Paleolithic in Europe [about 35,000 to 10,000 years ago] is linked with modern H. sapiens,” explained study co-author Jean-Jacques Hublin, a paleoanthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, to Live Science. “The artifacts of the transitional period have sort of mixed features.”One of the new studies examined LRJ artifacts, focusing on thousands of bone fragments associated with LRJ artifacts in Ilsenhöhle (Ilse’s cave) in Ranis, Germany. The research involved new excavations and analyses of remains found in the cave in the 1930s, shedding light on the intermittent use of the cave by both hominins and animals, such as denning hyenas and hibernating cave bears. The bone fragments were analyzed for their origins using proteins and DNA and were found to be from 44,000 to 47,500 years ago.Related: Scientists finally solve mystery of why Europeans have less Neanderthal DNA than East AsiansImage 1 of 2

The arrival of H. sapiens in Europe occurred after Neanderthals, who occupied the continent from around 200,000 years ago until their extinction roughly 40,000 years ago. Previous research indicated the presence of H. sapiens in Southwest Europe by 46,000 years ago. Much debate surrounds the interactions between H. sapiens and Neanderthals during the Middle-to-Upper Paleolithic transition period (47,000 to 42,000 years ago), and the potential role of H. sapiens in the decline of Neanderthals.The investigations of three new studies focused on artifacts and the climate from that transitional period. Archaeologists have previously identified various stone tool manufacturing styles from this time, such as the Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician (LRJ) industry, and questioned whether they were crafted by H. sapiens or Neanderthals.”The Middle Paleolithic in Europe [about 300,000 to 35,000 years ago] is linked with Neanderthals, while the Upper Paleolithic in Europe [about 35,000 to 10,000 years ago] is linked with modern H. sapiens,” explained study co-author Jean-Jacques Hublin, a paleoanthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, to Live Science. “The artifacts of the transitional period have sort of mixed features.”One of the new studies examined LRJ artifacts, focusing on thousands of bone fragments associated with LRJ artifacts in Ilsenhöhle (Ilse’s cave) in Ranis, Germany. The research involved new excavations and analyses of remains found in the cave in the 1930s, shedding light on the intermittent use of the cave by both hominins and animals, such as denning hyenas and hibernating cave bears. The bone fragments were analyzed for their origins using proteins and DNA and were found to be from 44,000 to 47,500 years ago.Related: Scientists finally solve mystery of why Europeans have less Neanderthal DNA than East AsiansImage 1 of 2

Ilsenhöhle (Ilse’s cave) is visible beneath the castle of Ranis. (Image credit: © Tim Schüler TLDA, License: CC-BY-ND 4.0)”The common wisdom was these transitional assemblages of artifacts were made mostly by late Neanderthals,” Hublin said. “What we find with the LRJ is that it was not made by Neanderthals but by Homo sapiens moving into Europe much earlier than we thought.”Chemical analyses and examination of animal teeth and bones indicated that H. sapiens lived in an area with very cold climates, resembling those found in Siberia or northern Scandinavia today. The surprising discovery challenges previous beliefs, suggesting that these human groups may have found cold steppes with larger herds of prey animals more attractive environments than previously appreciated.

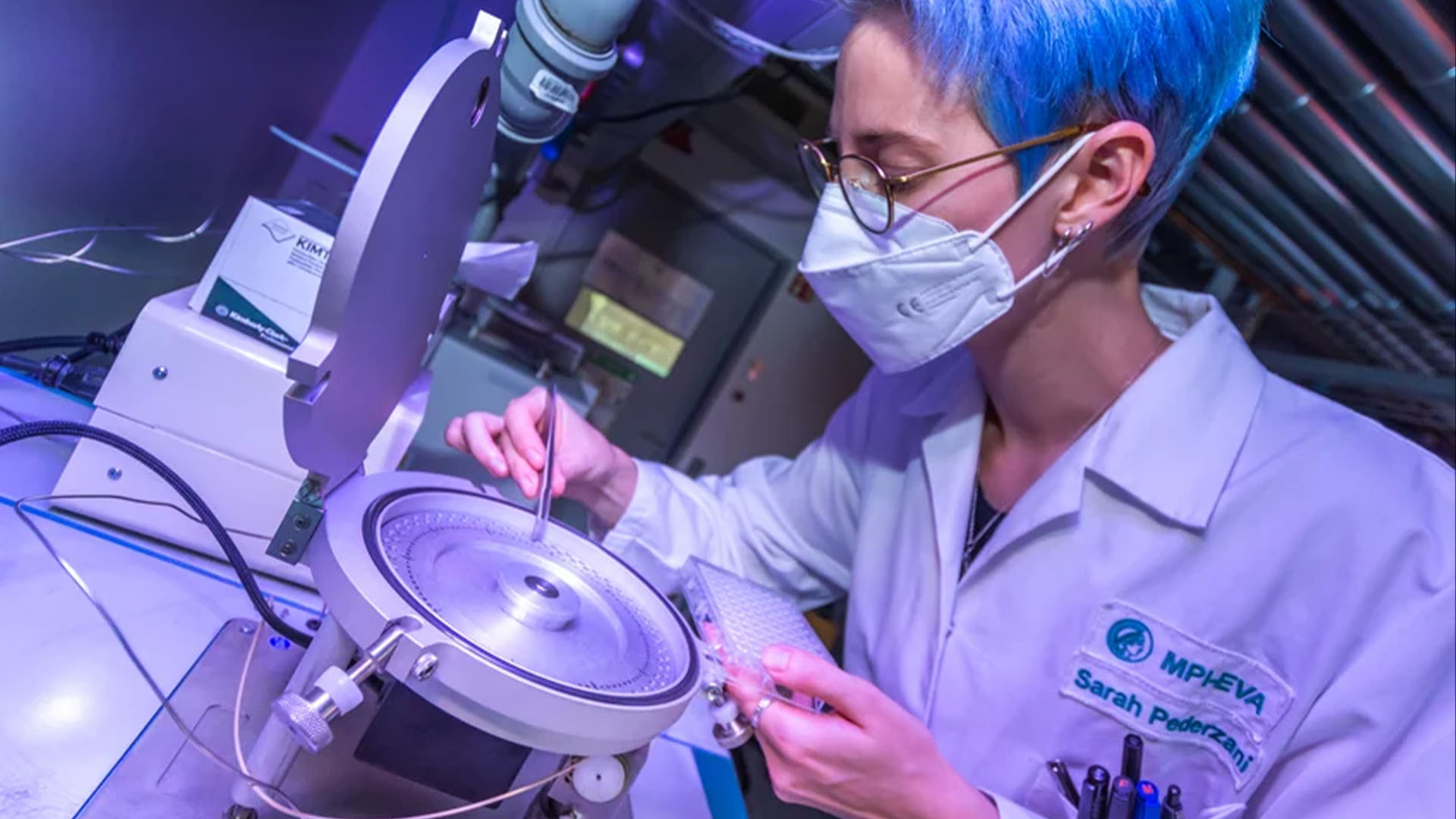

Ilsenhöhle (Ilse’s cave) is visible beneath the castle of Ranis. (Image credit: © Tim Schüler TLDA, License: CC-BY-ND 4.0)”The common wisdom was these transitional assemblages of artifacts were made mostly by late Neanderthals,” Hublin said. “What we find with the LRJ is that it was not made by Neanderthals but by Homo sapiens moving into Europe much earlier than we thought.”Chemical analyses and examination of animal teeth and bones indicated that H. sapiens lived in an area with very cold climates, resembling those found in Siberia or northern Scandinavia today. The surprising discovery challenges previous beliefs, suggesting that these human groups may have found cold steppes with larger herds of prey animals more attractive environments than previously appreciated. After chemical preparation and purification, research involved loading very small animal teeth samples into an isotope ratio mass spectrometer to obtain information about past climates that animals lived in. (Image credit: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, License: CC-BY-ND.)These findings suggest H. sapiens arrived in Northwest Europe several thousand years before Neanderthals disappeared in Southwest Europe, hinting at a potential interaction between the two groups. William Banks, an archaeologist with the French National Center for Scientific Research, commented on the complexity of the puzzle regarding the nature of interactions between H. sapiens and Neanderthals. The study challenges the previous belief of H. sapiens replacing Neanderthals in Europe in a rapid east-to-west wave, suggesting successive pulses of small groups moving into new territory and eventually replacing Neanderthals after several millennia. Future research could further investigate the origins of other transitions and examine Neanderthal remains for signs of Homo sapiens DNA.

After chemical preparation and purification, research involved loading very small animal teeth samples into an isotope ratio mass spectrometer to obtain information about past climates that animals lived in. (Image credit: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, License: CC-BY-ND.)These findings suggest H. sapiens arrived in Northwest Europe several thousand years before Neanderthals disappeared in Southwest Europe, hinting at a potential interaction between the two groups. William Banks, an archaeologist with the French National Center for Scientific Research, commented on the complexity of the puzzle regarding the nature of interactions between H. sapiens and Neanderthals. The study challenges the previous belief of H. sapiens replacing Neanderthals in Europe in a rapid east-to-west wave, suggesting successive pulses of small groups moving into new territory and eventually replacing Neanderthals after several millennia. Future research could further investigate the origins of other transitions and examine Neanderthal remains for signs of Homo sapiens DNA.