This is not going to be one of those articles that romanticizes the past, insisting that everything was better then and it will never be that good again. However, when it comes to newsrooms, that seems to be the reality.

“What would a newspaper movie look like today?” asked my colleague Jim Rutenberg from The New York Times. “A bunch of individuals at their apartments, surrounded by sad houseplants, using Slack?”

Mike Isikoff, an investigative reporter at Yahoo and my former colleague from The Washington Star in the ‘70s agreed, “Newsrooms were a crackling gaggle of gossip, jokes, anxiety, and oddball hilarious characters. Now we sit at home alone staring at our computers. What a drag.”

As my friend Mark Leibovich from The Atlantic notes, “I can’t think of a profession that relies more on osmosis and just being around other people than journalism. There’s a reason they made all those newspaper movies like “All the President’s Men”, “Spotlight”, and “The Paper”. There’s a reason people get tours of newsrooms. You don’t want a tour of your local H&R Block office.”

Leibovich admits that he now mostly works from home and says, “At the end of a Zoom call, nobody says, ‘Hey, do you want to get a drink?’ There’s just a click at the end of the meetings. Nothing dribbles out afterward, and you can really learn things from the little meetings after the meetings.”

When Leibovich got his first newspaper job at The Boston Phoenix, he soon learned that “the best journalism school is overhearing journalists doing their jobs.”

Isikoff still recalls how excited he was when he heard his seatmate, Robert Pear, the late, great reporter who later worked at The New York Times, track down the fugitive financier Robert Vesco in Cuba. “Hello, Mr. Vesco,” Pear said in his whispery voice. “This is Robert Pear of The Washington Star.”

With journalists swarming around Washington for the annual White House Correspondents’ Dinner and cascade of parties, it seems like a good time to write the final obituary for the American newspaper newsroom.

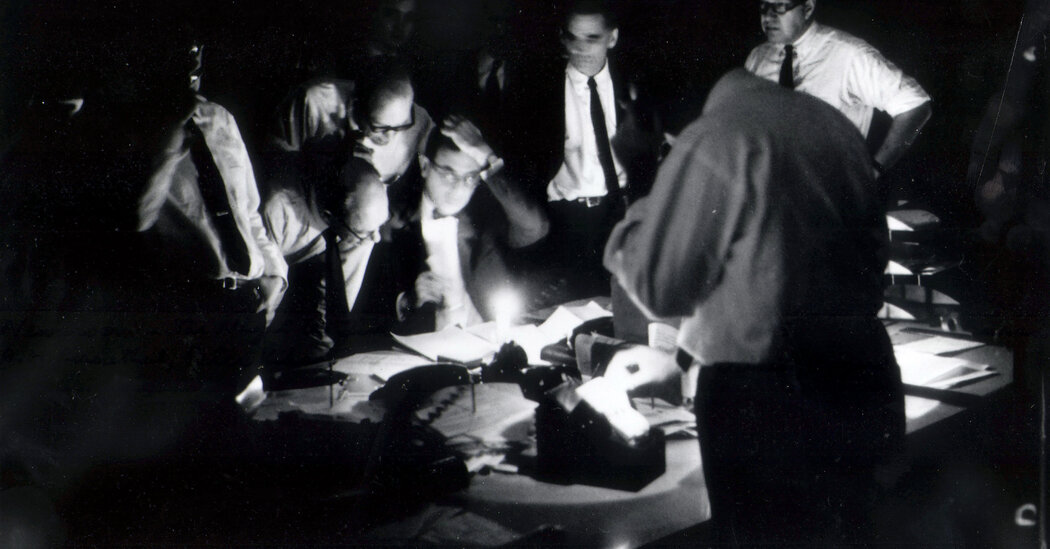

The atmosphere in a newsroom during the ’40s was well described by Arthur Gelb, the culture czar of The New York Times, in his memoir, “City Room”: “There was an overwhelming sense of purpose, fire and life: the clacking rhythm of typewriters, the throbbing of great machines in the composing room on the floor above, reporters shouting for copy boys to pick up their stories.” There was also a pungent aroma of vice: a carpet of cigarette butts, clerks who were part-time bookies, dice games, brass spittoons, and the occasional glamorous movie-star mistress wandering about. (The Times never went as far as Cary Grant’s editor did in “His Girl Friday,” putting a pickpocket on the payroll.)

Forty years later, when I started working in The Times newsroom, it was still electric and full of eccentric characters. There were no green eyeshades, and nobody yelled “Hat and coat!” to send you out to cover breaking news. It was quieter too, as computers had been introduced.

I had experienced a taste of the old louche glamour at The Washington Star. When I started, I was a clerk on the 9 p.m. shift; afterward, we would go to the Tune Inn, the only bar on Capitol Hill that would serve a Bloody Mary at dawn.

My job was to type up stories on my Royal typewriter, with carbon paper, dictated by reporters who called in from the field, including from the trial of the Watergate burglars. The newsroom could get rowdy, and it wasn’t just because mice occasionally ran across our keyboards.

Reporters had temper tantrums, smashing their typewriters or computer terminals on the floor, and an editor once sent me out for beer on deadline but then almost fired me when I brought back Miller Lite. Regardless, there was an incredible camaraderie and panache about the whole endeavor, whether we were covering stories about murder, politics, or the breeding woes of the pandas at the National Zoo.

“Conversation and competition turned newsrooms into incubators of great ideas,” said David Israel, my friend and The Star’s must-read sports columnist when I first met him.

As I write this, I’m in a deserted newsroom in The Times’s D.C. office. I’m thrilled to be back after working from home for two years during Covid, so I can wander around and pick up the latest scoop, but in the last year, there have only been a smattering of people whenever I’m here, with row upon row of empty desks. Sometimes a larger group gets lured in for a meeting with a platter of bagels.

Remote work is a major issue in contract negotiations for the Times union. They’re pushing for employees to work in the office no more than two days a week this year and three days a week starting next year. Management is concerned that young people who work remotely too often will become stagnant and see the institution as an abstraction, so they have committed to a three-day-a-week policy for this year but want to preserve the right to increase that in the future.

I worry that the romance and alchemy of the newsroom experience are gone. Once people realized that they could put together a great newspaper from home, they decided, why not? I appreciate the pleasure and convenience of working from home. I can set a fire, listen to Miles Davis and write at the dining room table while getting things done around the house.

“Let’s be honest,” says Ashley Parker, my former assistant who became a Pulitzer Prize-winning star at The Washington Post. “Political reporters have always