Before the existence of Neanderthals, Denisovans, or any primitive human-like primates, our earliest ancestors were microbes. More complex organisms, including us, originate from eukaryotes, which have a nuclear membrane around their DNA. The diversification of eukaryotes started around 800 million years ago, but a recent study led by UC Santa Barbara paleontologist Leigh Ann Riedman discovered microfossils of eukaryotes that are 1.64 billion years old. These microfossils had surprisingly advanced features, indicating that the eukaryotic clade has a much deeper history than previously thought.

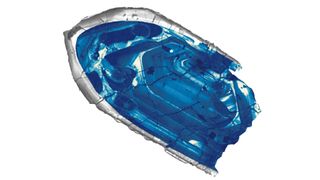

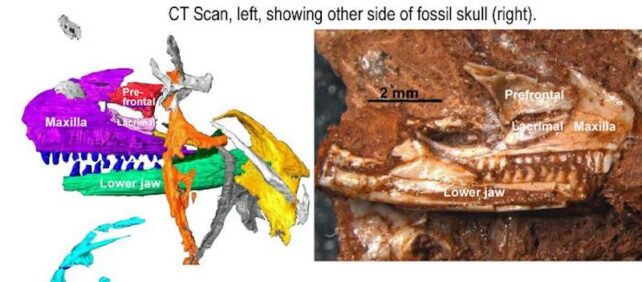

During the late Palaeoproterozoic era, eukaryotes likely evolved due to significant changes in Earth’s atmosphere and ocean chemistry. The researchers explored layers of sedimentary rock in Australia’s Birrindudu basin and found fossils of 26 taxa, including 10 previously undescribed species. One of these new species, Limbunyasphaera operculata, exhibited a feature reminiscent of a survival mechanism found in modern eukaryotes, indicating the advanced nature of these ancient organisms.

Some known species of extinct eukaryotes also surprised the researchers with their sophisticated features. For example, Satka favosa had a vesicle enclosed by a membrane with platelike structures, while Birrindudutuba brigandinia had plates around its vesicles. These discoveries suggest that ancient eukaryotes were much more sophisticated and diverse than previously thought, shedding new light on the early evolution of eukaryotic life.

The fossil evidence found by Riedman and her team suggests that eukaryotes have been much more complex and diverse for hundreds of millions of years longer than previously believed. These discoveries are providing valuable insights into the evolution of eukaryotes and, by extension, our own evolution.