For the past hundred years, cancer treatment has been focused on the location of the tumour in the body, utilizing surgery and radiation. Medical oncologists and other healthcare providers have categorized cancers based on the organ in which the tumour originated. However, this approach is no longer in line with the current developments in precision oncology, which uses molecular profiling to guide therapies.Furthermore, despite the traditional classification of cancer types, studies have shown that certain drugs, such as nivolumab, can effectively target specific molecular markers across various types of cancer. For example, nivolumab has demonstrated the ability to shrink tumours by more than 30% in some individuals, depending on the expression of the PD-L1 protein. This has led to a disparity in access to relevant drugs for individuals expressing high levels of PD-L1 in their tumours.

Thomas Powles: Cancer explorer

Thomas Powles: Cancer explorer

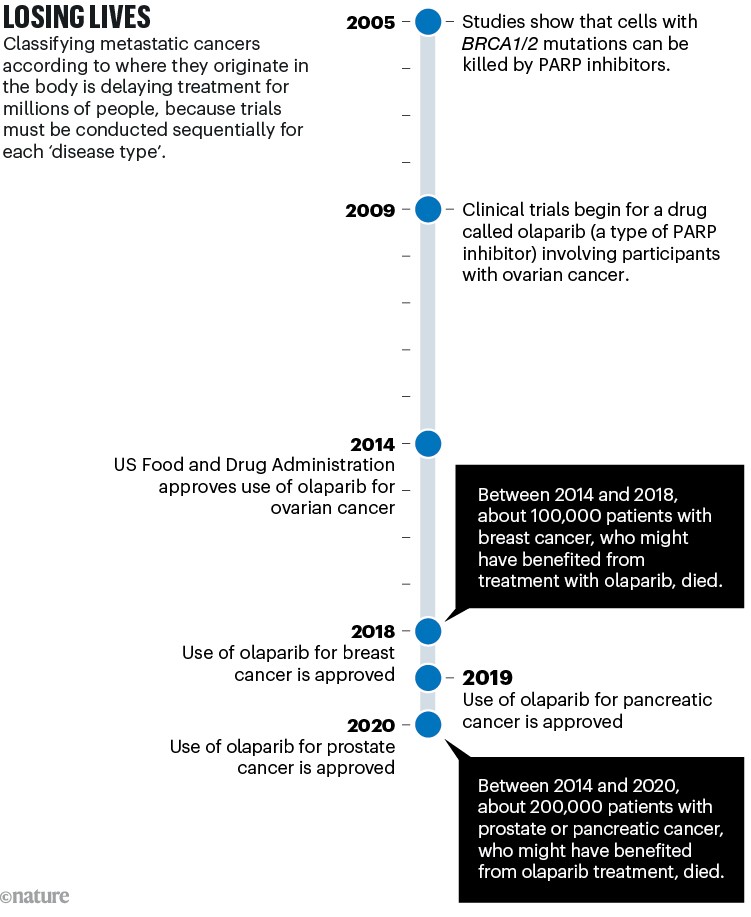

Clinical trials for different cancer types, conducted in sequence, have delayed access to potentially beneficial treatments for many patients. This has particularly affected individuals with high PD-L1 expression in certain breast or gynaecological cancers, who have had to wait 7–10 years to access PD1 inhibitors. Additionally, treatments such as PARP inhibitors, effective for tumour cells carrying mutations in breast cancer genes, have been restricted to specific cancer types, despite these mutations occurring in multiple cancer types.

Sources: BRCA–PARP: H. E. Bryant et al. Nature 434, 913–917 (2005); H. Farmer et al. Nature 434, 917–921 (2005). Olaparib trial: P. C. Fong et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 123–134 (2009). Ovarian approval: G. Kim et al. Clin. Cancer Res. 21, 4257–4261 (2015). Breast: Pancreas: Prostate:

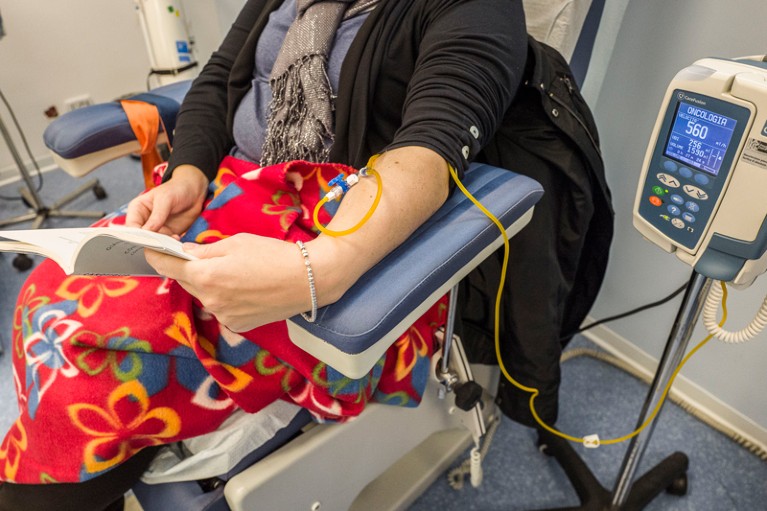

Metastatic cancers, accounting for a majority of cancer-related deaths, are primarily treated systemically, necessitating a shift from organ-based to molecular-based classifications of cancer for improved treatments. However, longstanding habits within the medical community and regulatory systems have impeded this transition. For example, patients in some European countries are not reimbursed for drugs tested across different cancer types. Medical oncology has been organized into multiple organ-specific specialties, further hindering progress.

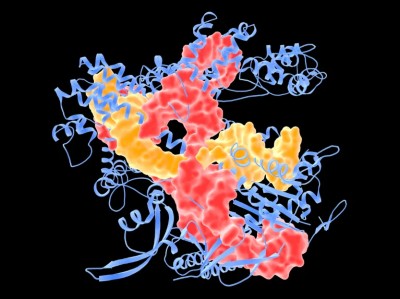

Physicians can identify molecular targets in individual cancers and decide on treatments.Credit: Gustave Roussy

In addition to impeding access to potentially life-saving drugs, the current classification of cancer also hinders medical education and patient comprehension. It disregards the shared molecular events driving the evolution of different cancer types and overwhelms students and practitioners with an excessive amount of information. Restructuring the approach by focusing on the molecular mechanisms could simplify learning and improve patient understanding.

The race to supercharge cancer-fighting T cells

The race to supercharge cancer-fighting T cells

At the same time, a molecular-based classification has the potential to improve treatment adherence and patient understanding. Such an approach would limit the amount of new information that patients need to comprehend and enable them to understand the biological mechanisms behind their treatment, ultimately increasing treatment adherence. Furthermore, classifying cancers based on their molecular characteristics would allow for personalized and more effective treatments for individuals.

People with cancers that have spread beyond the organ of origin are usually treated with drugs that enter the bloodstream.Credit: Fabrzio Villa/Getty

Steps to change the current approach include refining guidance and methodologies, restructuring oncology, rethinking education, and improving access to molecular testing. Regulatory agencies, scientific societies, insurance companies, and medical institutions need to redefine the evidence required to prioritize a specific molecular alteration over the organ in which cancer originated. Furthermore, restructuring oncology to focus on analysis of molecular profiles, rethinking medical education to equip students with a comprehensive molecular understanding, and ensuring widespread access to molecular testing are necessary to bring about this transformation.

CRISPR cancer trial success paves the way for personalized treatments

CRISPR cancer trial success paves the way for personalized treatments

Competing Interests

F.A.: Research Funding: AstraZeneca (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Eli Lilly (Inst), Roche (Inst), Daiichi (Inst). Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Novartis, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca. Ad boards or symposium compensated to the hospital: AstraZeneca, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Daiichi-Sankyo, Relay Tx and Roche. Ad board compensated to the author: Lilly. E.R.: Grants: Gilead (institutional); Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Pfizer, Roche, Mundipharma; Honoraria: Eli Lilly, Novartis, Lilly, Seagen. A.M.: Preclinical research funding from Fondation MSD Avenir. Clinical trial drug supply from Merck Sharp & Dohme. Clinical trial drug supply and funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb and Roche; personal fees, nonfinancial support from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol Myers Squibb, Astra Zeneca, Roche/Genentech, Sanofi, Glaxo Smith Kline, Pfizer, Johnson and Johnson. S.M.: Personal fees for statistical advice from Amaris, for Scientific Study Committee Membership from Roche, for data and safety monitoring membership of clinical trials from IQVIA, Sensorion, Kedrion, Biophytis, Servier, Yuhan.