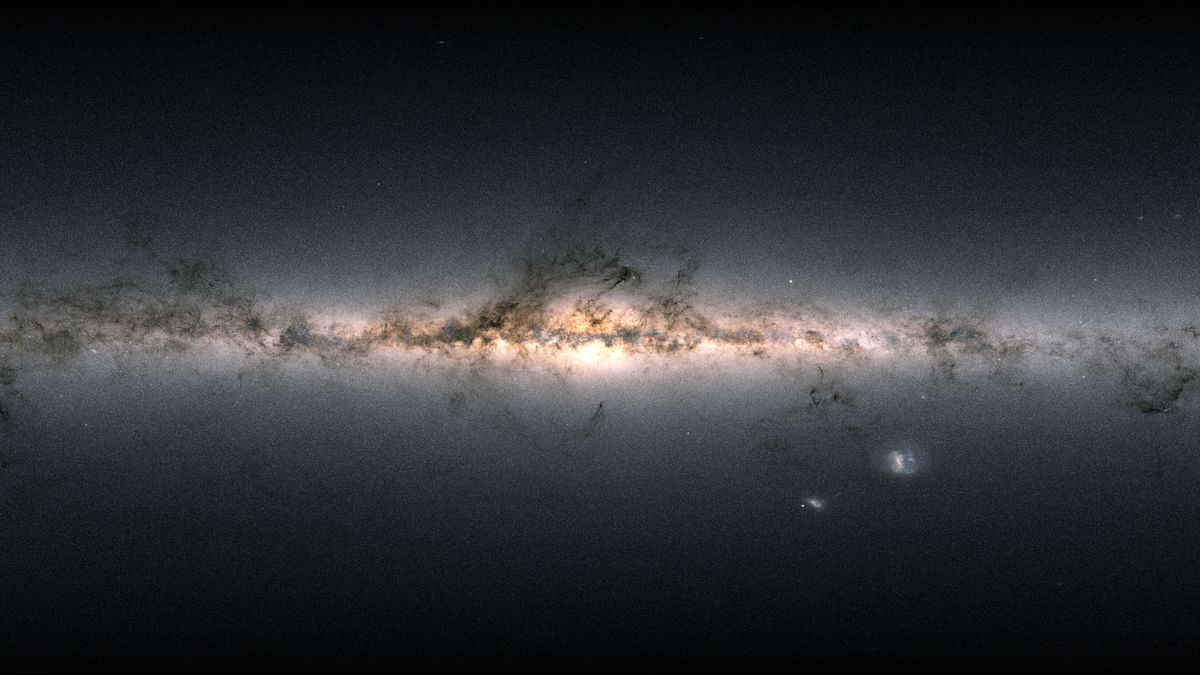

Far from the Milky Way’s center, stars are moving much slower than anticipated, perplexing scientists who suggest that the dark matter model of our galaxy may be flawed. The velocities of stars around galaxies’ edges have historically confirmed the existence of dark matter within those galaxies. This is because astronomers can plot a galaxy’s “rotation curve,” which shows the orbital speeds of stars compared to their distances from the galaxy’s center. In the absence of dark matter and its gravitational influence, stars would decelerate the farther they orbit from the galaxy’s center. However, in the 1960s and early 1970s, astronomers Vera Rubin and Kent Ford noticed that galaxies’ rotation curves remained flat, indicating that the orbital motion of stars did not decrease with distance. Scientists believe that this phenomenon can be explained by galaxies being enveloped in haloes of dark matter, which are most densely concentrated at the galaxy’s center, exerting gravitational force to keep stars in motion. Measuring the Milky Way’s rotation curve has proven to be challenging due to our position inside the galaxy, lacking a comprehensive view of it. Accurate distance information is required to determine the distance of various outlying stars from the galactic center. In 2019, Anna-Christina Eilers led a research team using the Gaia mission to measure the orbital velocities of stars up to 80,000 light-years from the galactic center, finding a flat rotation curve with a slight decline in velocity for the outermost stars. Combining Gaia measurements with those from Apache Point Observatory Galactic Evolution Experiment (APOGEE), researchers have obtained measurements for the Milky Way’s rotation curve for stars up to about 100,000 light years. Surprisingly, the curve remained flat up to a certain distance before decreasing in velocity, indicating that the outer stars are rotating slower than expected. This suggests there is less dark matter at the galaxy’s center than assumed, resulting in a “cored” dark matter halo resembling an apple. The team also notes that there is insufficient gravitational force from the existing dark matter to extend all the way to 100,000 light years and maintain stars’ velocity. These findings present a challenge to other measurements, suggesting an inconsistency that requires further investigation to provide a comprehensive understanding of the Milky Way. Next, the researchers plan to use high-resolution computer simulations to model various dark matter distributions within our galaxy to determine the best fit for the declining rotation curve. This will allow models of galaxy formation to explain how the Milky Way achieved its specific distribution of dark matter and why other galaxies did not. The findings were published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society on Jan. 8.

Something ‘fishy’ is happening with the Milky Way’s dark matter halo