Erika Zaid

The male dusky antechinus can lose up to three hours of sleep per day during mating season.

CNN

—

Sleep is a priority for many, but for a small marsupial in Australia, sex takes precedence over sleep. Male antechinus in Australia have been found to trade sleep for reproductive activities during mating season, with one male monitored during the period halving his sleep time.

The study, published Thursday in the journal Current Biology, is the first to demonstrate direct evidence of this “extreme” sleep restriction in any land-dwelling mammal, according to the researchers.

Erika Zaid, lead author and animal behavior researcher at La Trobe University in Melbourne, explained, “Animals need to reproduce to pass on their genes, but they also need to sleep to survive.” Zaid further stated that long-lived animals like humans and elephants do not face the same pressure to reproduce quickly, allowing them the luxury of sleeping as much as they want or need each day.

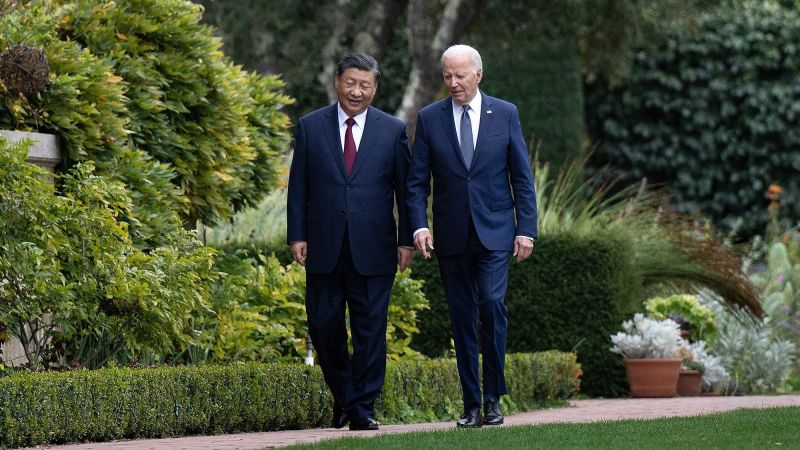

Francesca Leonard

Lead author Erika Zaid holding a dusky antechinus, 15 of which were observed in the study.

Unlike their female counterparts, male antechinus are semelparous, meaning they can only breed once in their lifetime, making prolonged sleep a luxury that could cost them their chance to pass on their genes. Non-breeding dusky antechinus spend an average of 15.3 hours of the day asleep, according to the researchers.

“Sleep restriction in breeding male antechinus is likely to be an adaptive behavioral response driven by strong sexual selection,” the paper explained. This drives them to compete with other males to reproduce with as many females as possible, before dying shortly after their first — and last — mating season.

Researchers studied two antechinus species: dusky antechinus (Antechinus swainsonii) and wild agile antechinus (Antechinus agilis) both in captivity and in the wild.

Males from both species were not only more active during mating season but also slept less during the same period, the data showed.

Males were found to sleep three hours less per night, every night, for three weeks — approximately the length of the mating period. Males, which only live for 11 months, reproduce once in their lifetime before dying, while females can reproduce more than once, Zaid said.

“Sleeping three hours less per night impacts waking performance in humans, (while) antechinus did this for three weeks. Therefore, antechinus may be resilient to sleep loss and have an unknown mechanism to thrive on less sleep during this time, or they may accept the physiological costs of staying awake to secure paternity before they die,” according to John Lesku, associate professor of zoology at La Trobe University and a sleep scientist, who was involved in the study.

The paper suggested that sleep reductions were due to the reproductive pressures on the males during their only breeding season, with increased sexual activity positively related to increases in testosterone, the male sex hormone, during the same period.

Using accelerometers — instruments used to measure the acceleration of a moving body — the researchers tracked the movement of 15 dusky antechinus (10 male) before and during mating season.

Researchers obtained blood samples to measure any changes in hormones and took electrophysiological recordings from four males to measure how much they were sleeping.

Blood samples were also taken from 38 wild agile antechinus (20 male) to see if oxalic acid, a biomarker for sleep loss, similarly decreased during the mating period.

While the decrease in oxalic acid suggests the agile antechinus were sleep deprived during mating season, the results show that the difference between males and females was not significantly different, which Zaid points out may suggest that females in the wild are similarly sleep deprived due to male harassment during the mating period.

Erika Zaid

Cool Temperate Rainforest in southern Australia where dusky and agile antechinus lose sleep for sex during the breeding season.

“Our study is the first to compare male and female activity levels before, during, and after the breeding season, and to reliably relate restfulness with sleep using accelerometry, electrophysiology, and metabolomics,” researchers said in the paper.

Volker Sommer, a professor of evolutionary anthropology at University College London, told CNN: “It rather seems that this is some pre-breeding stalemate in not letting one’s guard down: males are forced to stay awake because their competitors also do.” Sommer was not involved in the study.

While the results do not pinpoint a reason for the post-breeding male die-off, there are multiple possibilities, such as elevated corticosteroids — steroid hormones — and sleep deprivation.

Lesku said researchers would next like to examine how male antechinus deal with restricting their sleep for three weeks.

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.