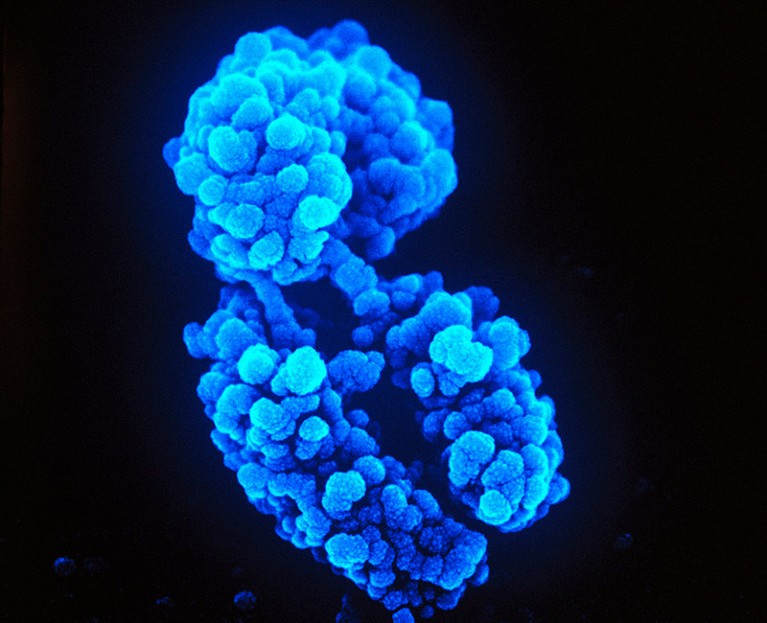

The female bias in autoimmune diseases might be due to the presence of a molecular coating on half of a woman’s X chromosomes, which is absent in males’ cells. This coating, consisting of RNA and proteins, plays a crucial role in X-chromosome inactivation. While the role of sex hormones and flawed gene regulation on the X chromosome in autoimmune diseases has been previously recognized, the discovery that proteins involved in X-chromosome inactivation could trigger immune responses adds a new layer of complexity. This finding could lead to new diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities, according to Laura Carrel, a geneticist at the Pennsylvania State College of Medicine in Hershey. The study unveiling this discovery was published in Cell1.Mystery SolvedThe mystery behind why women are more prone to autoimmune diseases than men, accounting for approximately 80% of cases, has puzzled immunologists and rheumatologists for decades. The presence of two X chromosomes in females, compared to one in males, has been a suspected contributing factor. In most mammals, including humans, one of the X chromosomes in female cells is inactivated, ensuring that the dosage of X-linked genes is similar to that in male cells. The inactivation process involves a physical mechanism where XIST, a long RNA strand, wraps around the chromosome, resulting in the formation of complexes with multiple proteins that effectively silence the genes. However, some genes escape this silencing, potentially causing autoimmune conditions. Additionally, the XIST molecule itself has been found to trigger inflammatory immune responses, as reported in 20232. But the whole story was yet to be uncovered.The XIST ProteinsUncovering a decade-old observation, researchers found that the proteins interacting with XIST were targets of autoimmune molecules known as autoantibodies. These autoantibodies can mistakenly attack tissues and organs, leading to chronic inflammation and damage characteristic of autoimmune diseases. Since XIST is typically expressed only in XX cells, it seemed plausible that the autoantibodies targeting XIST-associated proteins could pose a bigger problem for women compared to men. To test this hypothesis, male mice, which do not normally express XIST, were genetically modified to produce a form of XIST that did not silence gene expression but did form the characteristic RNA-protein complexes. Inducing a lupus-like disease in these mice revealed higher levels of autoantibodies and increased immune cell activation, indicating a predisposition to autoimmune attacks and extensive tissue damage. The same autoantibodies were also identified in blood samples from individuals with lupus, scleroderma, and dermatomyositis, supporting the idea that XIST and its associated proteins play a significant role in autoimmune diseases.Immune-system OverdriveThe findings in mice were further validated by human data, with implications for disease management. Diagnostic tools targeting these autoantibodies could aid in detecting and monitoring various autoimmune disorders. Montserrat Anguera, a geneticist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, sees the human data as evidence that the mechanisms related to XIST observed in mice directly apply to human autoimmune conditions. She highlights the potential for using this information to expedite diagnosis and improve disease management.