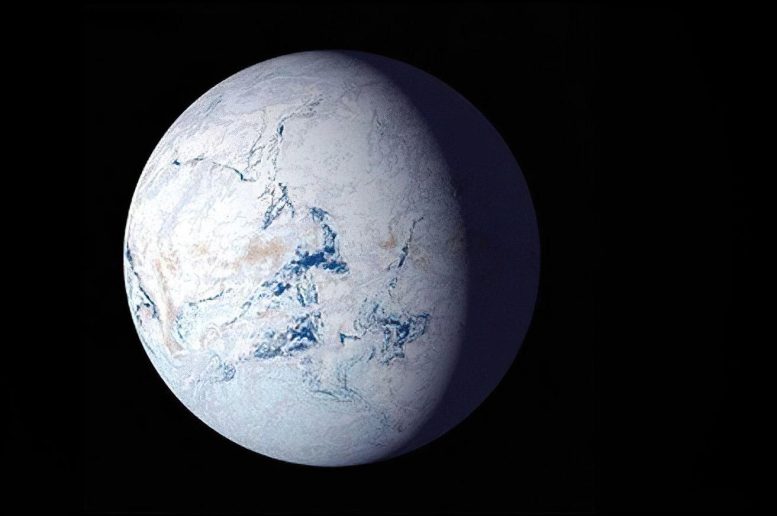

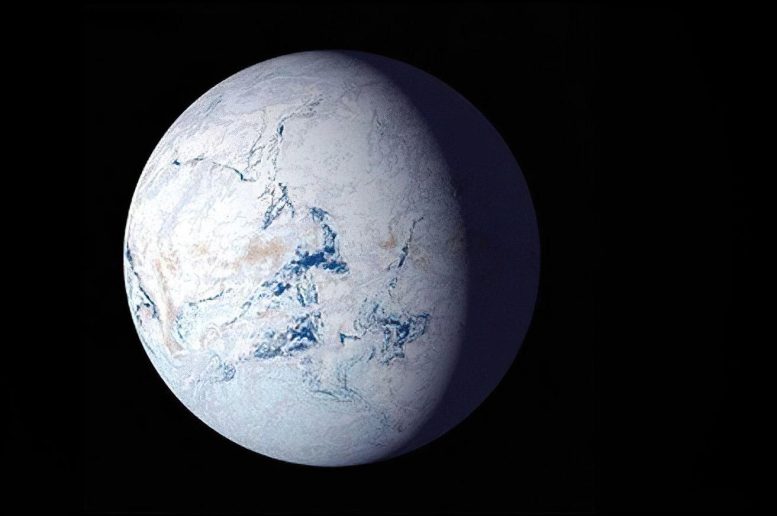

Geologists from Australia have identified the low emission of volcanic CO2 and rock weathering in Canada as important factors behind an extreme ice age that occurred over 700 million years ago. Their study, which used plate tectonic modeling and geological evidence from South Australia, sheds light on Earth’s climate sensitivity and its natural thermostat mechanisms, contrasting the slow pace of geological climate change with the rapid changes driven by human activities. Credit: NASAVolcanic carbon emissions reached a record low, leading to a global ice age that lasted 57 million years. Australian geologists utilized plate tectonic modeling to determine the most likely causes of an extreme ice-age climate that occurred on Earth over 700 million years ago. The research, published in Geology, enhances our understanding of the Earth’s built-in thermostat that prevents overheating. It also demonstrates how sensitive global climate is to atmospheric carbon concentration. “Imagine the Earth almost entirely frozen over,” said the lead author of the study, ARC Future Fellow Dr. Adriana Dutkiewicz. “That’s exactly what happened about 700 million years ago; the planet was covered in ice from the poles to the equator, and temperatures plummeted. However, the cause of this has been an unresolved question.

Geologists from Australia have identified the low emission of volcanic CO2 and rock weathering in Canada as important factors behind an extreme ice age that occurred over 700 million years ago. Their study, which used plate tectonic modeling and geological evidence from South Australia, sheds light on Earth’s climate sensitivity and its natural thermostat mechanisms, contrasting the slow pace of geological climate change with the rapid changes driven by human activities. Credit: NASAVolcanic carbon emissions reached a record low, leading to a global ice age that lasted 57 million years. Australian geologists utilized plate tectonic modeling to determine the most likely causes of an extreme ice-age climate that occurred on Earth over 700 million years ago. The research, published in Geology, enhances our understanding of the Earth’s built-in thermostat that prevents overheating. It also demonstrates how sensitive global climate is to atmospheric carbon concentration. “Imagine the Earth almost entirely frozen over,” said the lead author of the study, ARC Future Fellow Dr. Adriana Dutkiewicz. “That’s exactly what happened about 700 million years ago; the planet was covered in ice from the poles to the equator, and temperatures plummeted. However, the cause of this has been an unresolved question. Sturtian Glaciation glacial deposits from 717–664 million years ago in the northern Flinders Ranges, Australia, near the Arkaroola Wilderness Sanctuary. Lead researcher Dr. Adriana Dutkiewicz from the University of Sydney points to a thick bed of glacial deposits. Credit: Professor Dietmar Müller/University of Sydney”We now believe we have solved the mystery: historically low volcanic carbon dioxide emissions, along with weathering of a large pile of volcanic rocks in what is now Canada; a process that absorbs atmospheric carbon dioxide.” Geological Discoveries in the Flinders Ranges The project was sparked by the glacial remnants left by the ancient glaciation of this period, which can be prominently observed in the Flinders Ranges in South Australia. A recent geological expedition to the Ranges, led by co-author Professor Alan Collins from the University of Adelaide, inspired the team to utilize the University of Sydney EarthByte computer models to explore the cause and the remarkably long duration of this ice age.

Sturtian Glaciation glacial deposits from 717–664 million years ago in the northern Flinders Ranges, Australia, near the Arkaroola Wilderness Sanctuary. Lead researcher Dr. Adriana Dutkiewicz from the University of Sydney points to a thick bed of glacial deposits. Credit: Professor Dietmar Müller/University of Sydney”We now believe we have solved the mystery: historically low volcanic carbon dioxide emissions, along with weathering of a large pile of volcanic rocks in what is now Canada; a process that absorbs atmospheric carbon dioxide.” Geological Discoveries in the Flinders Ranges The project was sparked by the glacial remnants left by the ancient glaciation of this period, which can be prominently observed in the Flinders Ranges in South Australia. A recent geological expedition to the Ranges, led by co-author Professor Alan Collins from the University of Adelaide, inspired the team to utilize the University of Sydney EarthByte computer models to explore the cause and the remarkably long duration of this ice age.

Between 717 and 660 million years ago, the Earth was engulfed in snow and ice – a 57 million-year ice age. Geoscientists from the University of Sydney, led by Dr. Adriana Dutkiewicz and Prof. Dietmar Müller, have identified the probable cause: historically low levels of volcanic carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. This video depicts the movements of continents (grey) and plate boundaries (orange) from 850 to 540 million years ago. (Snowflakes appear during the ‘Snowball Earth’ periods.) Credit: Ben Mather and Dietmar Müller/The University of SydneySturtian Glaciation and Plate Tectonics The prolonged ice age, also known as the Sturtian glaciation after the 19th-century European colonial explorer of central Australia, Charles Sturt, spanned from 717 to 660 million years ago, a period well before the existence of dinosaurs and complex plant life on land. Dr. Dutkiewicz explained: “Various causes have been proposed for the onset and end of this extreme ice age, but the most puzzling aspect is why it lasted for 57 million years – a duration that is difficult for us as humans to imagine.” The team revisited a plate tectonic model that illustrates the evolution of continents and ocean basins after the breakup of the ancient supercontinent Rodina. They connected it to a computer model that calculates CO2 degassing of underwater volcanoes along mid-ocean ridges – the locations where plates diverge and new ocean crust is formed. Dr. Adriana Dutkiewicz from the School of Geosciences at the University of Sydney in the Flinders Ranges, South Australia. Credit: The University of SydneyThe Role of CO2 and Geological Climate Change They soon realized that the commencement of the Sturtian ice age closely corresponds with a record low in volcanic CO2 emissions. Furthermore, the CO2 outflow remained relatively low throughout the entire duration of the ice age. Dr. Dutkiewicz noted: “During this period, there were no multicellular animals or land plants on Earth. The atmospheric greenhouse gas concentration was mostly determined by CO2 outgassing from volcanoes and by silicate rock weathering processes, which absorb CO2.” Co-author Professor Dietmar Müller from the University of Sydney stated: “Geology dictated the climate at that time. We believe the Sturtian ice age began due to a combination of factors: a reorganization of plate tectonics led to a minimum in volcanic degassing, while simultaneously, a continental volcanic region in Canada began eroding, absorbing atmospheric CO2.

Dr. Adriana Dutkiewicz from the School of Geosciences at the University of Sydney in the Flinders Ranges, South Australia. Credit: The University of SydneyThe Role of CO2 and Geological Climate Change They soon realized that the commencement of the Sturtian ice age closely corresponds with a record low in volcanic CO2 emissions. Furthermore, the CO2 outflow remained relatively low throughout the entire duration of the ice age. Dr. Dutkiewicz noted: “During this period, there were no multicellular animals or land plants on Earth. The atmospheric greenhouse gas concentration was mostly determined by CO2 outgassing from volcanoes and by silicate rock weathering processes, which absorb CO2.” Co-author Professor Dietmar Müller from the University of Sydney stated: “Geology dictated the climate at that time. We believe the Sturtian ice age began due to a combination of factors: a reorganization of plate tectonics led to a minimum in volcanic degassing, while simultaneously, a continental volcanic region in Canada began eroding, absorbing atmospheric CO2. View towards the Arkaroola Wilderness Sanctuary, Flinders Ranges, with the Sturt Formation glacial deposits from the Sturtian Glaciation circa 717–664 million years ago forming a prominent ridge in the middle of the photo on the left. Credit: Professor Dietmar Müller/University of Sydney”The outcome was that atmospheric CO2 dropped to a level that initiated glaciation – which we estimate to be below 200 parts per million, less than half of today’s level.” The team’s research raises thought-provoking questions about Earth’s long-term future. A recent hypothesis suggested that over the next 250 million years, Earth would progress towards Pangea Ultima, a supercontinent so hot that mammals could become extinct. However, Earth is also presently on a course of lower volcanic CO2 emissions as continental collisions intensify and the plates decelerate. Thus, Pangea Ultima might eventually become an ice planet once again. Dr. Dutkiewicz remarked: “Whatever the future holds, it is essential to note that geological climate change, as studied here, occurs extremely slowly. According to NASA, human-induced climate change is transpiring 10 times faster than any previous rate.” Reference: “Duration of Sturtian ‘Snowball Earth’ glaciation linked to exceptionally low mid-ocean ridge outgassing” by Adriana Dutkiewicz, Andrew S. Merdith, Alan S. Collins, Ben Mather, Lauren Ilano, Sabin Zahirovic, and R. Dietmar Müller The study was funded by the Australian Research Council.

View towards the Arkaroola Wilderness Sanctuary, Flinders Ranges, with the Sturt Formation glacial deposits from the Sturtian Glaciation circa 717–664 million years ago forming a prominent ridge in the middle of the photo on the left. Credit: Professor Dietmar Müller/University of Sydney”The outcome was that atmospheric CO2 dropped to a level that initiated glaciation – which we estimate to be below 200 parts per million, less than half of today’s level.” The team’s research raises thought-provoking questions about Earth’s long-term future. A recent hypothesis suggested that over the next 250 million years, Earth would progress towards Pangea Ultima, a supercontinent so hot that mammals could become extinct. However, Earth is also presently on a course of lower volcanic CO2 emissions as continental collisions intensify and the plates decelerate. Thus, Pangea Ultima might eventually become an ice planet once again. Dr. Dutkiewicz remarked: “Whatever the future holds, it is essential to note that geological climate change, as studied here, occurs extremely slowly. According to NASA, human-induced climate change is transpiring 10 times faster than any previous rate.” Reference: “Duration of Sturtian ‘Snowball Earth’ glaciation linked to exceptionally low mid-ocean ridge outgassing” by Adriana Dutkiewicz, Andrew S. Merdith, Alan S. Collins, Ben Mather, Lauren Ilano, Sabin Zahirovic, and R. Dietmar Müller The study was funded by the Australian Research Council.

Unraveling a 700-Million-Year-Old Climate Puzzle: How Earth Became an Ice Planet