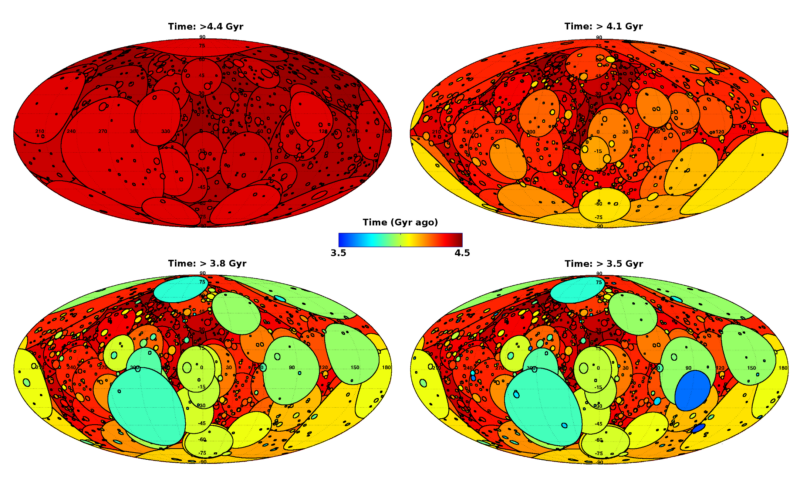

Enlarge / The graphic shows the modeled effects of early Earth’s bombardment. Circles show the regions affected by each impact, with diameters corresponding to the final size of craters for impactors smaller than 100 kilometers in diameter. For larger impactors, the circle size corresponds to size of the region buried by impact-generated melt. Color coding indicates the timing of the impacts. The smallest impactors considered in this model have a diameter of 15 kilometers.Simone Marchi, Southwest Research Institute

Earth has a history of being hit by asteroids, with two major events standing out—the one that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago and the one that formed the Moon. The asteroid that led to the dinosaurs’ extinction was just 10 kilometers in diameter, while the impactor that formed the Moon may have been as large as Mars. Between these significant events, Earth was also battered by other celestial bodies.

During the 2023 Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union, scientists discussed the effects of asteroids that struck early Earth, causing widespread melts and ancient tsunamis.

Creating melt

When the colossal impactor that formed the Moon collided with Earth, a large portion of the planet became a sea of melted rock, known as a magma ocean. After this event, there were no more major additions of mass to Earth, according to Simone Marchi, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute who creates computer models of the early Solar System and its planetary bodies. Despite this, there was still debris flying around. Although there may not have been another lunar-scale impact, there were likely large incoming asteroids. Predictions suggest that there were a substantial number of objects larger than 1,000 kilometers in diameter.

However, there is little direct evidence in the rock record of these impacts before about 3.5 billion years ago. Therefore, scientists like Marchi look to the Moon to estimate the number of objects that collided with Earth.

Advertisement

Marchi and colleagues used the size and number of impactors to build a model that describes the volume of melt that these impacts must have produced at the Earth’s surface over time. While magma oceans were a thing of the past, impactors larger than 100 kilometers in diameter still melted a significant amount of rock and would have drastically altered early Earth.

Unlike smaller impacts, the volume of melt generated by objects of this size isn’t confined to a crater. Any crater formed would only exist momentarily, as the rock is too fluid to maintain any structure. Marchi likens this to throwing a stone into water. “There is a moment in time in which you have a cavity in the water, but then everything collapses and fills up because it’s a fluid.”

The melt volume is much larger than the amount of excavated rock, allowing Marchi to calculate how much melt might have spilled out and coated parts of the Earth’s surface with each impact. The result is an astounding map of melt volume. During the first billion years or so of Earth’s history, nearly the entire surface would have been covered in a layer of impact melt at some point. Much of this history has been lost due to the constant modification of the rock record by Earth’s atmospheric, surface, and tectonic processes.

Glass balls

Even between 3.5 and 2.5 billion years ago, the rock record is incomplete. However, evidence of impacts in the form of spherules is preserved in two places—Australia and South Africa. These tiny glass balls form immediately after an impact that sends vaporized rock into the atmosphere. As the plume returns to Earth, small droplets start to condense and rain down.

Nadja Drabon, Harvard

Nadja Drabon, Harvard

“It’s remarkable that we can find these impact-generated spherule layers all the way back to 3.5 billion years ago,” said Marchi.